Special to the Armenian Weekly

From Izmir and Sivrihisar to Cyprus, to seek a safer home with better prospects… but that came to an end in December of 1963, and again after the Turkish invasion of Cyprus in July 1974—yet another in a series of displacements for genocide survivors.

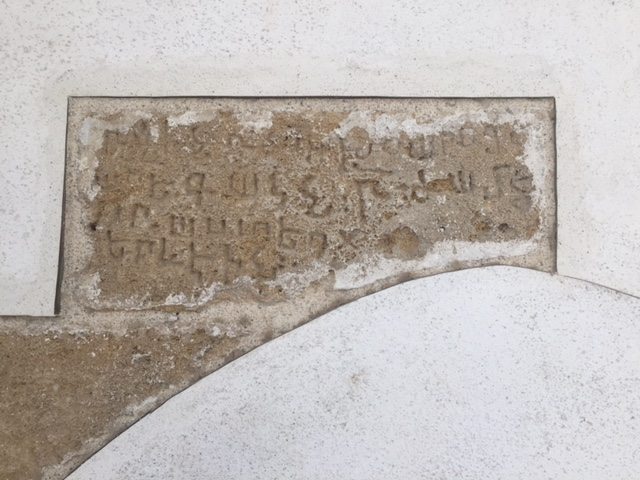

The Sourp Asdvadzadzin Church in Turkish-occupied Nicosia, Cyprus has been occupied since 1963 (Photo: Lori A. Sinanian)

Our family decided that this summer we would travel one more time together, since our trajectories would diverge in the coming years due to our different schedules. The destination we decided on was—the island of Cyprus, my grandfather’s and father’s birthplace, including the Turkish-occupied northern part of Կիպրոս (Kipros), and a place where Turks, Armenians, and Greeks once lived together. Though we stayed in a coastal town in Larnaca for most of our time, far from the Green line between the Republic of Cyprus and the Turkish occupied Northern Cyprus, we dedicated two days to visit Nicosia (Lefkosia in Greek) a street less than a mile away from northern Nicosia, which is now occupied by the Turkish military, in the so-called Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus—recognized only by Turkey, the invader state.

“Welcome to the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus” reads a sign (Photo courtesy of an anonymous submission to the Armenian Weekly)

“In 1963, Zaven’s and my family had been forced out of our homes by the Turkish Cypriots, who had created their own enclaves in each of the towns in Cyprus as a result of the Turkish-Cypriot uprising. The Armenian community suffered major losses, including houses, shops, as well as community immovable property, such as the Sourp Asdvadzadzin Armenian Church, prelature, school, and club on Victoria Street,” recalled Vahan, one of my father’s closest childhood friends.

To cross-over to the other side (i.e., Northern Cyprus), my father, mother, brother and I, led by Vahan Aynedjian, my father’s classmate from elementary school— we parked Vahan’s vehicle a few blocks away from the military checkpoint separating the Greek and Turkish sides of Nicosia.

“Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus Forever” reads a sign at the checkpoint (Photo courtesy of an anonymous submission to the Armenian Weekly)

Our first stop, the Cyprus Republic (Greek) checkpoint. We passed through easily by identifying that we were human beings—simply by waving to the guards. At the second checkpoint, I noticed the building’s 1950s-era awning featuring distinctive red and white stripes, vertically patterned. Above the awning, there was a sign that read, “Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus FOREVER.” At that point, I knew exactly where we were. The term “forever” is a pretend, make-believe concept, and so I found it to be a form of humor, but for them a serious moral purpose defined the term.

The five of us were asked to show identification. After checking in, we were asked to “make sure to check out and show identification once more before exiting.” The officer at the checkpoint continued, “If one of you does not check out, that means no one is allowed through until the person who has not checked out is found.”

After crossing the two checkpoints on the neutral zone—the Green Line, as it is better known—between the Cyprus Republic and the occupied north, we walked to Victoria Street, which now has a Turkish name, and entered a narrow street where we came upon a security guard who let us in to see the church where my grandparents were married and my father was baptized, which he most gladly did, saying: “Church… open.”

When we walked into the church yard Vahan recalled: “Your father and I had been christened in this church back in 1961. Our parents would have had a shared dream for us—that we would go to the same kindergarten in the churchyard, and then to the adjacent Melikian-Ouzounian elementary school. However, all those dreams were shattered. These premises were captured by the Turks, and for 40 years they were left unmaintained, ready to collapse. Fortunately, in 2003, when the so-called borders opened, the Armenian Diocesan Council pressed for the renovation of the complex, and through the intervention and financing of the United Nations Development Program UNDP and USAID respectively, a major renovation program was executed, saving the buildings from total ruin. Though the Turkish-Cypriot authorities allow the Armenian community to have a ceremony in the church once a year, it is doubtful that the Diocesan Council, as the rightful owners of the property, can have any type of jurisdiction over them for the near, foreseeable future. While chances of the Cyprus problem being solved remain remote, we will have to be unwillingly content with occasional visits to the north” said Vahan.

“When we walked into the church yard Vahan recalled: ‘Your father and I had been christened in this church back in 1961.’” (Photo: Lori A. Sinanian)

As we were leaving the church the guard asked us what language we were speaking, and we said Armenian. He said he was also part Armenian on his grandfather’s side. How ironic that the Turkish guard at the Armenian Church occupied by Turkey had Armenian origins. Sadly, we did not speak Turkish, and his English was poor so we could not communicate with him to learn more about his Armenian roots.

“As we were leaving the church the guard asked us what language we were speaking, and we said Armenian.”

Walking the streets of Northern Cyprus while listening to Vahan’s voice in the background as he provided historical context, I began questioning reality, criticizing and contrasting everything. I was experiencing an increasing sense of alienation from the present moment, allowing me to live in the past, among the competing forces: Greeks and Armenians against the harsh reality of the Turkish invasion in 1974 that upset life on this paradise. I was metacognitively thinking… about my thinking. At some point, I was completely detached and disrupted by my emotions that took me away from that moment. An emotion in my mind had me stuck in the past. I kept telling myself that I must observe and draw back, as opposed to becoming involved emotionally. It’s almost like these thoughts and feelings were already embedded in my brain and in my body, and they had suddenly just started waking and working. It all became so real. The silence experienced in unison among us five felt loud. I was yearning for something emotionally fulfilling, and so I found beauty in being distracted by my raw emotions—by not focusing on concrete, intimate, imaginary, images of my Armenian great-grandparent survivors of the genocide, and grandparents and parents forcibly removed from their homes—while walking the streets where our history had died again. The detachment I was experiencing was to learn an already-discovered truth: All that occurred was based on tangible reality—what was right in front of me.

The entrance to the court of the Armenian Church, the Der Hayr’s home, and the Armenian school (Photo: Lori A. Sinanian)

“It is saddening that your father and I cannot remember anything from 1963, as we were only two and three years old, yet these places mean so much to us and our lost history in the post-genocide Armenian neighborhoods of Nicosia,” said Vahan.

Source: Armenian Weekly

Link: Northern Cyprus as Trauma Redux