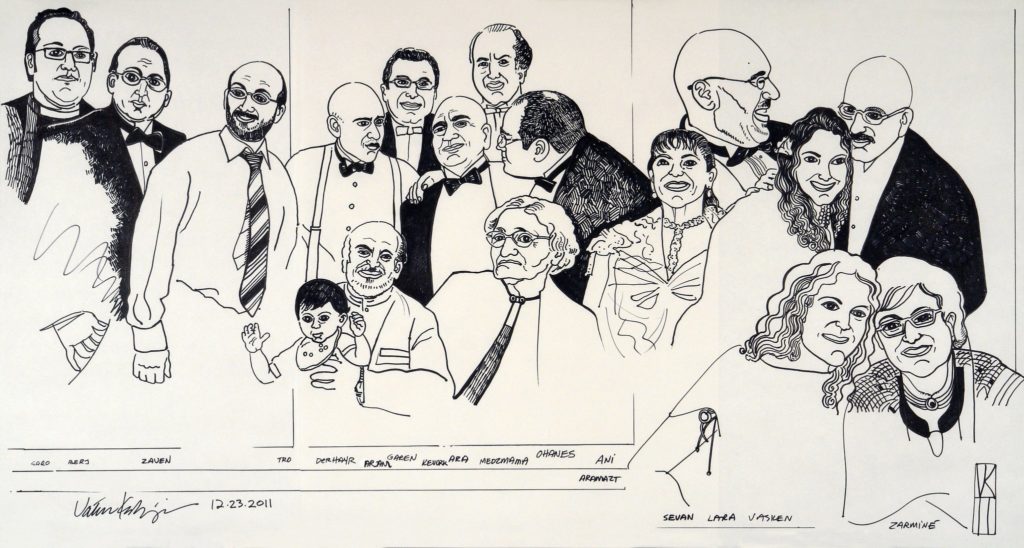

Growing up as a child of two Syrian immigrants of Armenian descent, I had access to multiple clandestine languages that perfumed the ether of my childhood. Both my parents were Middle Eastern city-slickers, raised in the bustling business center of Aleppo, with the exception of my father, who spent his early days in Azez, a village north of the big city. When they arrived to the United States, both of them had a limited understanding of English, although with some education and a little bit of cash. Family gatherings felt like a slurry of Voltron and Transformer talk, with my cousins and force-feeding family members and reprimanding the non-use of the Armenian language. Scolding over language was commonplace and the best revenge was reciting a poem from memory whose words were everything to the elders and absolutely nonsensical to me. But their responses were as sweet and endearing as the first sip of strong coffee, praise in ecstasy. This ecstatic endearment was reserved for only the brave, who would venture out beyond their conception of shame and fear to speak incorrectly and to stand corrected. Many friends have confessed over the years having regretted succumbing to such shame owing to the aforementioned language-based reprimands.

The celebration of the Armenian language amongst diaspora communities is a thread finely and tightly interwoven into the fabric of our understanding of culture. Mathematical, spiritual, historical and survival attributes are showered to these 36 awkward characters. I can recall my father dangling flash cards in my crib, labeling spices and shoe racks with Armenian identifiers in order to further the process of linguistic immersion. And it worked—at least, for Armenian.

Yet there was a plethora of other languages that I always regretted not inquiring about. Levantine Arabic (most prominently spoken in Lebanon, Syria, and parts of Iraq) was their lingua operandi for most of my parents’ childhood and adolescence. Yet the only remnants of this language to trickle down to me were curse words (which, more often than not) involved the mothers’ and aunts’ holiest of holies and the occasional self-deprecating curses for giving birth to a troublemaker son like me.

My mother learned French at the Catholic school in Aleppo (yet not quite to the extent where she felt comfortable in her knowledge of the language to use it in conversation), but her preferred clandestine language was Turkish.

After a small gathering of my aunts at our home, the children would be shooed away to play outside or elsewhere and on our way out, we could hear the whisperings of gossip, cloaked in the language of the “enemy” (or, tshnamoo lezoon, as it is said in Armenian). It didn’t matter what language they gossiped in—the body language and hushed undertones so characteristic of gossip is universal: Who wore what to church? Who said what to whom at the Christmas bazaar? Such information remained a mystery, as it was shrouded in the language forbidden to me by my paternal uncles.

This practice, of speaking Turkish to keep certain conversations private, has waned over the years, but my memories of it have not, especially the sayings repeated often in childhood, by parents and grandparents living in northern Syria. These sayings often are the punchlines to longer parables or aphorisms that are derived from spiritual texts, and sometimes dirty jokes They are also a reflection of an oral history—of street smarts, where echoes of Turks to Armenians, Armenians to one another, parents to children, can be heard in just a few words. Below is a collection of a few Turkish sayings in my Armenian memory, without analysis, without interpretation. Feel encouraged to imagine your own context of who would be uttering these words, who would be listening and who may be eavesdropping…

Sen salla başını ben bilirim işimi

Hang your head, I know my work

Göt öpmekle ağız kirlenmez

Ass kissing makes for a dirty mouth

Çok karıştırma boku çıkar

Don’t mix it up too much the shit will come out

Annem olsun ağzı olmasın babam olsun eve gelmesin

Give me a mother who doesn’t speak, give me a father who doesn’t come home

Çok söyleme arsız edersin, aç bırakma hırsız edersin

If you coddle them they’ll get sassy, if you leave them hungry they’ll thieve

Oyle olmaz sade boyle olmazdı, boyle oldı daha iyi oldı

If it didn’t happen that way, it wouldn’t have happened better this way

Eşeğin aklına karpuz kabuğu düşürmek

For the memory of the donkey, the watermelon rind is temptation

Dönen dönsün ben dönmezem yolumdan

Whatever happens, I will never change (Literally: Let those who stray away do so, I will never stray from my path)

Şeytan gelmez adamını yollar

Satan doesn’t come but sends man away

Parayı veren düdüğü çalar

Money makes the duduk play

Iş başka, dostluk başka

Work is one thing, friendship is another thing

Herkese şapur şupur bize yarabbi şükür

Sharing with everyone but not with me

Tembele iş varmişler akıl vermiş

A lazy person’s job is giving opinions (Literally: They employed a lazy person and he provided them intellect)

Kızım sana söylüyorum, gelinim sen anla

Speaking to my daughter, hoping daughter will understand (Literally: My daughter I’m telling, understand your bride)

Author information

The post Turkish: The Secret Language of My Childhood appeared first on The Armenian Weekly.

Source: Armenian Weekly

Link: Turkish: The Secret Language of My Childhood