By Knarik O. Meneshian

From the Armenian Weekly 2016 Magazine

Dedicated to the 101st Anniversary of the Armenian Genocide

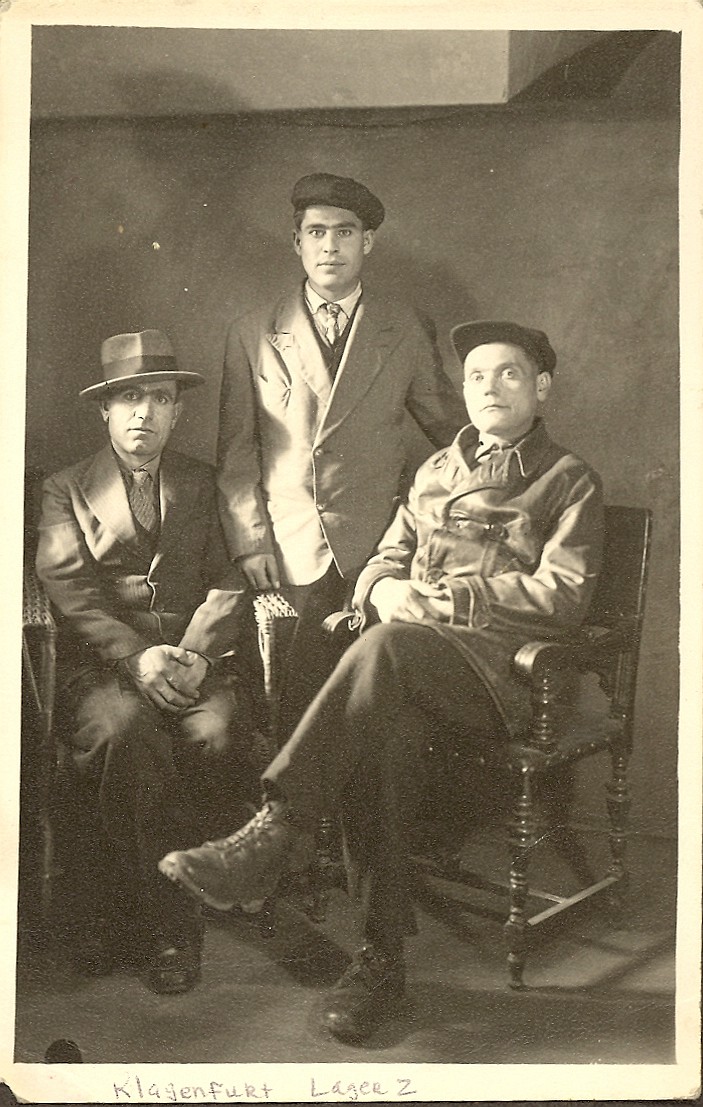

This story—of Armenian Displaced Persons (DP) in Europe during and after World War II—began to take shape with an old photo I have of three men pictured in the Armenian section at the Weidmannsdorf Lager C of the DP Camp in Klagenfurt, Austria. One of them is my father. Although the three men were POWs and slave laborers, their life in the camp—even with the meager food rations and harsh living conditions—was a haven for them and the other Armenians in the DP Camps in Germany and Austria. My father’s story offers a glimpse into the life and times of these Armenians who eventually, through the assistance of the American National Committee to Aid Homeless Armenians (ANCHA), made America, and other countries, their home—far from the land and loved ones they had been forced to leave.

The Communist takeover in Armenia and in the other countries that became a part of Stalin’s “Utopia” drastically altered the life of the people. No longer were they allowed to own homes, businesses, or belongings of any kind. To make matters worse, taxes were increased to such an extent that efforts to pay them often times became impossible. In this manner, not only was the upper class destroyed, but also the middle class. As a result, a three-class-system was instated. The most favored class, the ones who had nothing, mainly the laborers and shepherds, were considered “a cornerstone of socialism.” The next class, those who owned a few goats and chickens and a couple of cows, were considered a “half-hearted ally of socialism.” Those who were slightly better off than the first two classes were considered the “enemies of socialism.” To maintain Soviet “equality,” the rich and middle classes were exiled to Siberia, and those who were opposed to collectivism “were either sent to prison or never heard from again.” In this new and ‘The Happy Life’ Under Stalin’s Sun, (‘Yerjaneek Gyankuh’ Staleenyan Arevee Dak, Hairenik Amsagir, Boston, Mass., January to December, 1966), my father, Suren Hovhannesian, describes his experiences and the political situation during the years 1920-45. He also describes his life as a political prisoner in Stalin’s Siberian and other prisons throughout the vastness that was the Soviet Union, as well as his life as a POW, slave laborer, and DP in Europe.

Born in Armenia’s rugged Syunik region and orphaned as a young child, Hovhannesian grew up to become a teacher, writer, and political activist during Stalin’s reign. He and other young men who disagreed with this new “equality” and the censorship of a person’s every word and movement, the spying, even in the prisons, on one another, as well as the eradication of rights and the confiscation of property, were arrested as “enemies of the state” for writing and distributing pamphlets criticizing the new regime. Hovhannesian spent years in Siberia’s political prison, as well as in prisons in Tiflis (Tbilisi), Tashkent, Samarkand, Ufa, Alma-Ata, and Moscow.

How the prisoners, both men and women, survived the horrific and nightmarish conditions in those hellholes is impossible to comprehend, other than to believe that this was a most ruthless testing ground for the “survival of the fittest.” The conditions in the prisons were inhuman—overcrowded and disease ridden. Food and water were scarce, and there was a lack of toilet facilities, but there was always an abundance of torture. Many died in those dark and dank hellholes. During the summer months, “thousands of insects were everywhere,” which made the conditions even more unbearable. The prisoners subsisted on one meal a day, which consisted of no more than two small slices of half-baked bread and warm water with a few slivers of cabbage in it. Sometimes, they were given salted fish bones.

“From 1930 to 1935, millions of civilians were murdered, deported, or exiled to die in the frozen tundra of Siberia. Their only ‘crime’ being that they owned a cow, or a couple of goats, or a house,” describes Hovhannesian. The prisoners were from all walks of life. Some were intellectuals; some were villagers. They were charged with having taken part in “anti-revolutionary activities,” purportedly in support of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF). In numerous instances, the Cheka (Soviet Secret Police) set up elaborate plots through which they could test the loyalty of the people, especially that of the rural folk. In an attempt to deceive the people even further, they also spread false rumors. Because of their devious undercover activities, the Cheka collected “evidence” that resulted in the imprisonment of countless innocent people.

Among the countless innocents was an Armenian from America who had left his comfortable and secure life behind and moved his thriving furniture business to Yerevan in 1925-26 in the hopes of assisting his parental homeland. A few years after setting up his business, his property and assets were seized, and he was thrown into prison. There, like many others, he languished in his overcrowded cell and became nothing more than a breathing skeleton who sat motionless day and night, while lice swarmed up and down his body, and in and out of his long hair and beard, which had grown together into a tangled mess. His clothes, which long ago had disintegrated into shreds of filthy, rotten rags, were all that was left of his worldly possessions. He had become an unrecognizable human being, an apparition with only his eyes offering any expression of life.

Another innocent Armenian prisoner, who was originally from Turkish-occupied Armenia, had been beaten so severely that his eye had to be removed because the Cheka had smashed it. From one village, 120 men had been gathered and thrown into prison; their crime was “displaying their dismay” of the Soviet regime. In his memoir, my father recalls an event that took place in the women’s cell, across from the men’s. He describes the long and agonizing cries of a woman in labor followed by the cries of a newborn. The infant’s cries could be heard day and night. Then, suddenly, a week later, there was silence. No one ever found out what happened to the mother and child: Were they dead or taken away?

My father wrote about many other situations. He described how the prisons were so overcrowded that it was impossible for the inmates, who slept on the ground, to sleep on their backs. They had to either sleep on their sides or sit with their backs against something or someone. A single bucket was assigned to each cell for the purpose of relieving oneself. Every morning that bucket would be taken away, and a bucket of water would be brought in. That water was to be used for both drinking and washing up. The precious water that was consumed by many was reserved for drinking only. No one even thought of washing themselves. Shuffled from one prison to another, prisoners never knew when they would be gathered and shot to death.

One day years ago, when my father and I were talking about his life, as we did from time to time, he explained, “My prison escape in Siberia happened by chance. I felt that I was on the verge of dying and decided that it was better to die escaping than to die rotting in prison. I waited and looked around as I wondered how I was going to escape. Only one or two out of a thousand were able to escape from Stalin’s prisons—Stalin, ‘the father of all the people!’ Then, one day, the guards in the area where I was assigned to work were not at their stations. It was their ‘off day’ and in their place was a skeleton crew. In such an instance, the guards, occasionally, would be somewhere else. In such a situation, one never knew when a guard would return—perhaps in a second or two, perhaps in a minute or two. Suddenly, a tiny voice within me screamed, ‘If you are going to escape, do it now! You will never have a better chance!’ I obeyed that little voice in me and disappeared into the Siberian landscape.”

Whenever my father and I talked about his life in Stalin’s prisons, he would always say with profound thankfulness, as tears welled in his large, green eyes, “If it were not for the courage and kindness of the Russian people—the country folk—I would never have succeeded, or survived. At great risk to themselves and their families, they hid me in their homes long enough for me to warm up and eat the food they graciously offered. After quickly eating, they would say, ‘Please hurry…any moment someone can come! There are eyes and ears everywhere!’ As I would quickly leave—for in no way did I want to endanger their lives any more than I already had—with a bow of my head, I would always express my deep gratitude to them. They in turn, in kind and gentle voices would say, ‘God be with you!’ Their meager rations consisted of bread and watery cabbage soup. In their eyes, in the tone of their voices, and the clenching of their jaws, they made it known that they despised the regime that had reduced them to muzzled, shackled, starving slaves. They wanted no part of Stalin’s ‘Utopia.’ They knew I was not Russian, for unlike most of them I had black hair and an olive complexion. They knew that the tall, gaunt man in rags standing before them was an Armenian. All of those courageous and selfless souls—from the Russian country folk to the young Russian soldier and the Cheka officer—at great risk to themselves helped me, a stranger, a fugitive they knew nothing about other than I was in dire need. I will never forget their words, ‘God be with you,’ which I believe guided me to freedom.”

The Armenian section of the Klagenfurt DP camp. My mother and father standing behind the group of Armenian men.

After his flight from captivity, my father lived under an assumed name and for a while, as he described, “a relatively peaceful existence,” though he always looked over his shoulder and carefully measured his every spoken word. He explained, “In early 1942, with the onset of World War II, I was called to duty in the Soviet Army. Later in the year, I was assigned to a battalion combating the Germans. There were fierce ground and air bombardments, and we were attacked on all sides. We were ordered by our commander not to retreat without orders, no matter what. Most of the men in my division were killed; those that survived were severely injured. The Germans took us captive in 1942. We became POWs and slave laborers. We worked in various places—Dalmatia, Germany, Poland, Ukraine. We worked 12-18 hours a day, either near shipyards where we took ammunition to the German ships, or on the railroads where we unloaded wood and coal, or sometimes unloaded ammunition, from the train cars. The work was hazardous. Above, the Allied planes flew. We even worked in the forest, where they stored barrels of gasoline. One night, the bombers targeted us, and many perished, among them 15-out-of-30 Armenians and 40 other prisoners I was working with. In Poland, which had a great many war prisoners of all nationalities, I remember well the kindness of the Polish people; they gave us food to eat, even money.”

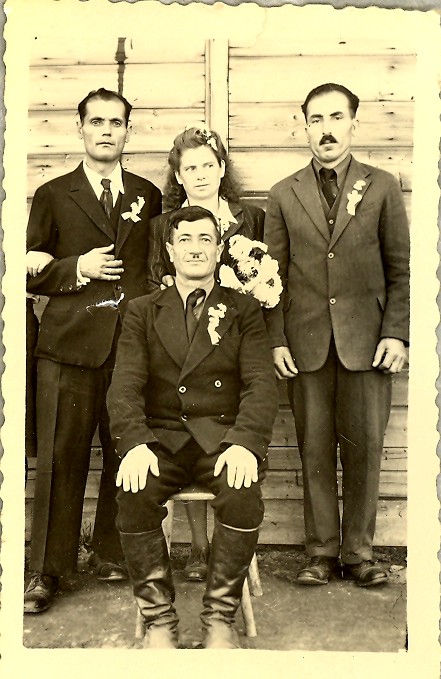

The Armenian All Saints Church Hall, Chicago. Flowers and an appreciation dinner to honor and thank George Mardikian.

“In May of 1945, the Germans took us to Klagenfurt, Austria, and surrendered us to the British. Not long after, the British told us to report to the Red Army barracks for repatriation. We were warned that if we did not do so, they would forcibly surrender us. As a member of the Red Army in the early years of World War II, I witnessed with my own eyes the horrific brutality of the Soviet authorities towards Red Army soldiers who had fallen captive to the Germans. These soldiers, who had defied death to escape German detention to make their way back to the Red Army lines, met with a death sentence upon their return. Other Red Army soldiers, however, deserted and exerted effort to be captured by the Germans in order not to continue fighting for Stalin’s tyranny. These deserters were in the hundreds of thousands. Facing the threat that I would be returned, without a doubt, to the Soviet Union—the place from which I had escaped under the most harrowing conditions—left me in an indescribable panic, for I knew that in no uncertain terms a death sentence awaited me, as it did my fellow Armenians and other POWs. Upon hearing this order, I quickly fled, obtained civilian clothing, and falsified my citizenship, as did many others, to prevent, by any means possible, being returned to the Soviets, and went to a DP Camp. The DP camps were under the auspices of UNRRA [the United Nations Refugee and Relief Administration]. I was now a Displaced Person—truly a man without a country, just like countless others. Words cannot adequately express the constant hardships the DPs suffered—the extreme difficulties of daily survival and the constant terror and anticipation of forced repatriation to the Soviet Union at any moment.”

Over the years, I had come to realize that my father was a born reporter and writer from the stories he told me of his life, including those during Armenia’s First Republic. He was always asking questions then, and if the conditions were unsafe or impossible for writing, he would “write notes” in his memory. Even when he was in the Soviet prisons, he asked questions of fellow prisoners. During his escape, he asked the people he met, and those who helped him, questions. Sometimes, my father would talk to me about the conditions of the DP camps in Germany and Austria after the war. He would explain, while every so often gently shaking his head, that the camps were filled with refugees—people who had been forcibly taken from or fled the Soviet Union. All of them lived in terror that at any moment they would be returned to where they came from. The camps—wooden barracks—were overcrowded and teaming with bedbugs, fleas, and lice. Filth and illness were everywhere. Food and proper clothing were scarce, and the barracks were drafty and cold. There were no blankets, mattresses, or even pillows on the crudely built double-decker beds. Men, women, and children were mixed together. Despite the appalling living conditions, the people were content and thankful, just as long as they did not have to return to the Soviet Union.

After the war, my father worked for a few years as a laborer in several European countries. In Klagenfurt, Austria, he succumbed to tuberculosis and was hospitalized. That is where he met my mother, a nurse assigned to his care. When they eventually married (he was in his forties, and she was in her twenties), she joined him in the DP camp. Together my parents, and other Armenians and their brides, most of whom were Austrian, made the camp their home. To this home, the women brought beauty and cheerfulness in glasses filled with wildflowers they would pick. During those difficult days, people who did not work were not given food coupons. This applied to children and babies as well.

After I was born, and at the age for regular food, my parents shared their meager rations with me. One Christmas, though, my parents managed to get me a priceless gift—an orange! At times, because of illness due to the harsh and difficult living conditions and lack of food, my parents could not always care for me, so arrangements were made for me to be cared for by others—families, kind strangers in Austria, in France, in Germany. Our camp was situated in the British zone. The Allied Agreement had divided Austria into four zones: the British, the French, the U.S., and the Soviet. Living conditions, as mentioned, were extremely difficult, and the people suffered from severe malnutrition and many diseases. They were dusted with DDT in order to stop the spread of typhus fever. My mother contracted the dreaded disease. Eventually, we and other Armenians were moved to the Funkerkaserne (Funker Bunker) near Stuttgart, Germany.

All along, during the war, certain members of the ARF, among them Drastamad Kanayan (Dro) and Misak Torlakian, were active in rescuing Armenian POWs and civilians of the Soviet Union and Europe from German captivity. Kanayan was an Armenian military commander and served as the defense minister of Armenia in 1920, during the country’s brief independence. Torlakian, who witnessed and knew first-hand the sufferings of the Armenians, for his family had been killed in the 1915 genocide, empathized with the people they were rescuing. In 1921, Torlakian was found innocent by a British court in Constantinople for assassinating Azerbaijan’s interior minister, Behbut Khan Jivanshir. The minister had ordered the massacre of the Armenians in Baku and Karabagh/Artsakh. Misak Torlakian’s book, Oreroos Hed (Horizon Publication, Los Angeles, Calif., 1953) describes the plight of the Armenian POWs and the DPs, and life in the DP camps.

In his book, Torlakian explains how he and Dro moved freely throughout Germany, Romania, Ukraine, and Crimea searching for and rescuing Armenian POWs and civilians. For example, the two men, along with other comrades, rescued 40 Armenians from a POW camp near Bucharest. In Simferopol, Crimea, the Germans released a group of 200 Armenian POWs and civilians to them. In Feodosia, Crimea, the men rescued 60 POWs; in Kerch, Crimea, they rescued 350 Armenian POWs—all released to them; in Germany, 400 Armenians from Greece were rescued by the men, as were many others in German and Austrian camps. A total of 3,000 Armenians from German-occupied territories were rescued by Dro, Torlakian, and their comrades, and brought to safety.

In his book, Torlakian also explains that the Germans deported mainly POWs and unemployed civilians to work as slave laborers in Germany. To avoid the deportation of unemployed Armenians in Crimea, Dro’s men opened a bakery, which produced enough bread to feed the Armenians. They also opened a barbershop, a sewing shop, a shoe shop, a coffee house, a grocery store, a restaurant, and other businesses totaling 16 in all. Part of the income from these businesses was donated to the local church and school, and a certain amount was used to entertain the German officers.

Eventually, Dro, Torlakian, and others who aided in the rescue efforts were able to draw the attention of American officials to the desperate situation facing Soviet Armenians and the aggressive and forceful methods being used by the Soviets to return them to the Soviet Union. As a result, in October 1945, the Americans allocated the former German dilapidated Funkerkaserne military camp near Stuttgart, Germany, for use by the Armenians.

Torlakian describes in detail the life of the DPs at the Stuttgart camp, and the amazing resolve and industriousness of these battered refugees in cleaning and repairing, within a short period, the dilapidated military barracks that was to be their home for several years. In 3 months’ time, for example, all 480 broken windows at the Funkerkaserne were repaired. The American personnel were amazed by the transformation. Before the end of 1945, there were 1,413 people of all ages at the camp. Classrooms were set up for 250 students up to the 7th grade. A hall for lectures, theatrical presentations, and orchestral performances was prepared. A church was established, and the Very Reverend Vahan Asgarian, ordained in Etchmiadzin, Armenia, was the camp priest. Occasionally, Archimandrite Grigor Shahlamian, the prelate of Germany, visited the camp. After Asgarian’s death in 1948, Shahlamian also became the camp clergyman.

The camp community opened carpenter, barber, shoe, and radio-repair shops. The camp administration opened a driving school, set up a needle-works class, and built bathhouses and public restrooms. They established a printing press and published papers. Those who were physicians established a medical clinic. In early 1948, a chapter of the Armenian Relief Society (ARS) and a boy’s scouts group were formed. At the beginning, American soldiers policed the camp, but after one month, this responsibility was turned over to the Armenians. Disagreements and problems were resolved at the camp by a judicial group, which was elected by the camp population. The camp had its constitution approved by the camp population and verified by the American authorities. By the end of 1951, there were 78 weddings and 142 births (my baby brother among them).

In 1947, George Mardikian, a San Francisco restaurateur, himself a Genocide survivor, seeing the plight of the Armenian DPs in Europe and learning of the many who committed suicide rather than allowing themselves to be returned to the Soviets, determined—along with Suren Saroyan and other compassionate and generous Armenians—to aid these unfortunates. In the book Our Brothers’ Keepers: The American National Committee to Aid Homeless Armenians (ANCHA) (The Armenian Apostolic Church of America, N.Y., 2012), Prof. Hratch Zadoian describes the founding of the ANCHA, its work, the selfless people and organizations who made it a success, and the extraordinary efforts that went into aiding the Armenians in the DP camps of Europe.

Zadoian poignantly describes the resilient nature of the Armenians who had experienced Stalin’s “Utopia” and their eventual placement in Europe’s DP camps. A number of them, over time, were taken to the Funkerkaserne. There, as described earlier in Torlakian’s account, the Armenians not only cleaned and repaired the camp, but also transformed it into a mini Armenian city. “On a sub-freezing December day, Mardikian was taken to the Funkerkaserne, a former German army barracks that was bombed during the war and now served as an Armenian DP camp,” writes Zadoian. “There Mardikian found some 2,000 Armenians: children and the elderly, workers, artists, peasants, musicians, academics, craftsmen, actors, doctors, housewives, merchants, and writers…” After outlining the accomplishments of the people in the camp, the piece continues: “In sum, they had everything that could be had with creativity and hard work under the circumstances. But they had no future and no reason for hope.”

The Armenian All Saints Church Hall, Chicago. Flowers and an appreciation dinner to honor and thank George Mardikian.

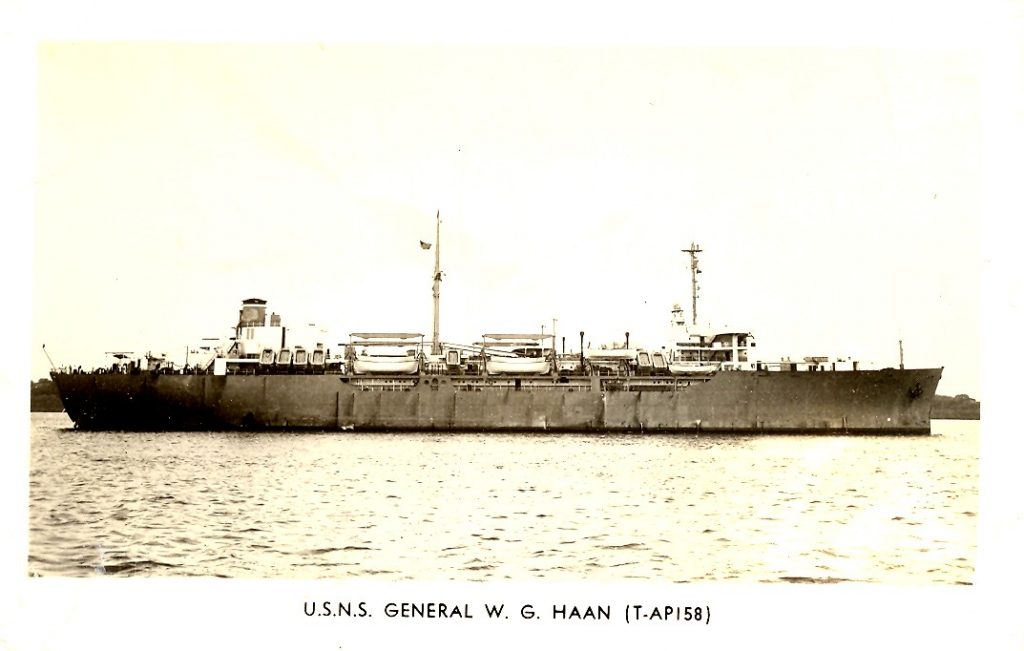

With the assistance of the ANCHA, my parents, brother, and I, along with other DPs, boarded the U.S.N.S. General W. G. Hann in the fall of 1951 for the United States of America. According to my parents, the ocean voyage was difficult. The weather was fierce and cold, and as a result, many people became ill. Since it was a military ship, the passengers were in charge of cooking, serving, cleaning, and looking after the sick. All able-bodied passengers were assigned specific tasks on a rotating basis. Our destination, after reaching New York, was Chicago. In Chicago, representatives of the local ARS chapter met us at the bus stop, put us in a cab, and handed my father the address of our new home: the second floor of a two-flat apartment building owned by an Armenian family. Once again, like the birds in springtime, we would make a new home—finally, a peaceful and permanent one in America. In America, where there were Armenian communities, churches, centers, and schools; where the DPs, forever longing for their Armenian homeland, could join fellow Armenians from other places in making a “homeland” away from the homeland.

Armenian DPs with wives and children in the Klagenfurt DP camp. My father in the front bottom of photo holding my playmate and I; my mother at the very top.

The World War II Armenian DPs in Chicago—one of the many “bereft and endangered DPs of the 40s,” Zadoian writes—never forgot what George Mardikian and the other selfless people had done for them. A few years after our arrival, Mardikian visited Chicago. The DPs welcomed him at a dinner in the basement of the Armenian All Saints Apostolic Church (then located on LeMoyne Street in Chicago) with open arms and tears of profound thankfulness. A bouquet of flowers was presented to him.

A few years after Mardikian’s visit, Misak Torlakian came to Chicago to visit and spend time with the DPs. He was a soft-spoken, quiet man with a gentle smile and sorrowful eyes. During his visit, my father, the Eastern Armenian, and Torlakian, the Western Armenian, often played chess together for hours, at times not uttering a word—just thinking and playing. The room would fill with cigarette smoke and we children dared not interrupt the men or make any noise. When the chess games were over, they would sit down to a typical Hayastantsi meal, and then quietly talk well into the night.

Source: Armenian Weekly

Link: A Glimpse into the Life of the Armenian DPs in Europe