Alevis in Turkey: A History of Persecution

November 21, 2016Special for the Armenian Weekly

Warning: This article includes graphic images some readers may find disturbing

Alevi Community Leader Attacked in Istanbul

Baki Duzgun, the President of the Alevi-Bektasi Federation, and some of his friends were attacked by a group local Muslims in the Sisli district of Istanbul on Oct. 22. “A group of about thirty people attacked us, shouting ‘Allahu akbar,’” wrote Duzgun on his Twitter account. “What happened last night can happen in Turkey anywhere, any time,” Duzgun added.

Indeed, physical and verbal attacks against Alevis, a religious minority in Anatolia, are commonplace in Turkey. Even their faith, Alevism, has not officially been recognized by the Turkish state, which has a “secular” constitution.

Oppression of Alevis in Turkey is legal. A law enacted by the founding government of Turkey, the Republican People’s Party (CHP), in 1925—which is still in effect in Turkey today—banned the religious centers of Alevis, including their houses of prayer, otherwise known as cem houses.

According to a parliamentary report in 2013, there are 82,693 mosques in Turkey, and only 937 cem houses. And 31 out of the 81 provinces in Turkey do not have a single cem house. Alevis try to build their places of worship with their own funds—with no government support.

Since the establishment of the Turkish Republic in 1923, Alevis in Turkey have struggled for official recognition and religious liberty, but their calls have not yet been heard. Instead, they have been exposed to several massacres and deadly attacks.

Some of the major massacres against Alevis in Turkey include:

1921 Kocgiri Massacre

The Kocgiri rebellion was launched in 1919 by the Kocgiri Alevi Kurdish tribe in the region commonly termed by Alevis “the Kocgiri region” that covers the Imranli, Divrigi, Hafik, Kurucay, Kangal, Refahiye, and Sariz districts in the cities of Erzincan, Dersim and Sivas.

Professor Taner Akcam writes that “the Kocgiri uprising in 1919-21 is an example of a Kurdish attempt at independence followed by repression.”

According to some sources, before the massacre, Nurettin Pasha—who led the Turkish military campaign—said, (claimed by other sources that these words belong to the Turkish militia leader Topal Osman): “In Turkey, we annihilated people who speak ‘zo’ (Armenians), I’m going to clean up people who speak ‘lo’ (Kurdish) by their roots.”

As a result of the Turkish military campaign, the Kurdish quest for freedom was brutally repressed in 1921. And not only Kurdish-Alevi freedom fighters but also civilians were murdered wholesale. Hundreds of Alevi Kurds were killed and thousands were forced to live in mountains in poverty.

“The Turks added Kurds and Greeks to their genocidal plans in the massacring of Armenians,” according to the scholar Shahkeh Yaylaian Setian. “The Kurdish attempt at independence in the Kocgiri revolt in 1919-1921 was answered with avenging massacres.”

1937-1938 Dersim (Tunceli) Massacre

The Dersim massacre was started on May 4, 1937 and lasted until 1938. “The decision to annihilate the people of Dersim was made by the Turkish Council of Ministers on May 4, 1937,” according to a press release of the Federation of Dersim Associations in Europe.

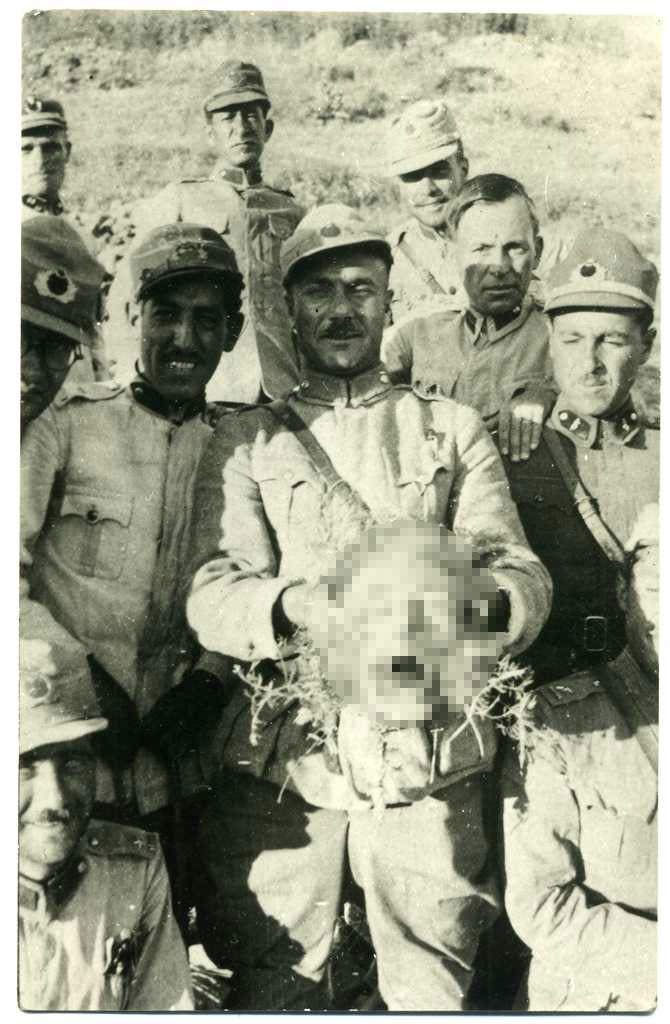

A photo from the 1937 Dersim massacre (Photo: From the archive of Hasan Saltik from Dersim, published in Sabah newspaper)

“The Turkish government bombed the territory of Dersim on the same day, and they killed hundreds of women, men, children and elderly people. Some families were scattered one by one in distant villages, towns or provinces. The leading figures of Dersim were hanged immediately and with no trial.” The victims were Alevi Kurds of the province. The ruling party at the time was the CHP, which ruled Turkey from 1923 to 1950, and the president was Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, the founder of modern Turkey.

1938 Erzincan Zini Gedigi Massacre

In the summer of 1938, the residents of a group of Alevi villages in the city of Erzincan were exposed to another massacre.

According to a statement by the “Zini Gedigi Initiative” made in 2014, about 100 Alevi boys and men were gathered from Surbahan and other villages (Mollakoy, Kismikor, Balıbey, Magacur and Girlevik) and were kept in the stable of Eyup Aga for three days.

The boys and men were then tied to one another and taken to a desolate place, the Zini Gedigi district between Dersim and Erzincan under the surveillance of Turkish soldiers. All of the captive Alevi boys and men were killed there on Aug. 6, 1938. The dead bodies were left there in the open and the families of the victims were exiled to western areas.

The region where the massacre took place was “a prohibited area” until 1950. After that, the villagers were finally able to go the region—and only to see the mass graves of their loved ones.

In 2011, the family members of the victims were able to go to court to demand that the officials “open the mass graves and give them the dead bodies”. Twenty-six days after the application, the prosecutor of Erzincan said that “the incidents were not genocide and they were related to public order” and he declared nolle prosequi due to “statute of limitations.”

1978 Malatya Massacre

The Malatya massacre started on April 17, 1978 and lasted for three days. Eight Alevis were killed and at least one hundred were wounded.

The Turkish nationalists used the assassination of the mayor of the city of Malatya as an excuse to provoke the Muslim residents of the city against Alevis. According to the witness statements published by Alevinet.com, this is how the massacre took place:

In the morning of April 18, when the attacks against Alevis were escalating, the Koran was being recited through the loudspeakers of the local mosque. Then a group of Turkish nationalists, during the day, were announcing repeatedly with loudspeakers: “We are losing our religion. They are putting bombs in mosques, too.” Around 20,000 people gathered in the city to attack Alevis.

The masked people among the crowd started attacking and burning down the houses, offices and businesses belonging to Alevis and left-wingers which had been marked beforehand. The aggressors also attacked and destroyed the buildings of some political parties, trade unions, associations, newspapers, printing houses, restaurants that sold alcohol, and stores.

A total number of 960 businesses and houses were damaged—100 of them were destroyed completely. Dozens of vehicles were also attacked. The cost of damages was estimated to be 100 million Turkish Liras.

1978 Sivas Massacre

Under the same government of the CHP led by Ecevit, another massacre was carried out against the Alevi community—this time in the province of Sivas. A group of fundamentalist Muslims and Turkish nationalists attacked the Alevi-populated Alibaba neighborhood on Sept 3-4, 1978.

According to the sociologist Feza Erdendogdu, twelve Alevis were killed and at 200 were wounded. More than 100 houses and workplaces belonging to Alevis were attacked and damaged and 75 people were detained.

1978 Maras Massacre

A closer look at the history of Turkey reveals that one of the most routine and consistent policies of the Turkish state has been to murder its Alevi citizens or turn a blind eye while they are attacked.

At least 105 Alevis were murdered in the city of Kahramanmaras, or Maras, in December 1978 by Turkish nationalists (otherwise known as Grey Wolves) and other fundamentalist Muslims.

“The actual perpetrators of the killings were not a small group of conspirators,” wrote Emma Sinclair-Webb, senior Turkey researcher with the Human Rights Watch. “They were ordinary people, villagers and townsfolk who became capable of horrific acts of torture and murder of young and old, women and men. The accounts of the killings bear out the fact that the question of religious affiliation became central as a means of deciding who needed to be purged. Witnesses testified in court that victims were frequently asked by their assailants to prove that they were Muslim and Turkish.”

According to official sources, at least 200 Alevi-owned houses were burnt down and 100 offices were attacked and damaged. A great majority of the Alevi population left the town after the incidents. Among the Alevi victims of the massacre was Esma Suna, who was shot to death in her eighth month of pregnancy.

The prime Minister of Turkey at that time was Bulent Ecevit, the “secular” leader of the CHP.

1980 Corum Massacre

The Corum massacre occurred between May and July of 1980. “The pretext was again religion,” wrote the scholar Tozun Issa. “The Alevis were ‘infidels’ and needed to be taught a lesson.

“Rumors were spread that Alevis were planning to bomb Sunni mosques. An agitated Sunni group was swiftly directed towards the Alevi district. As they left a mosque after Friday prayers, they were soon joined by armed gangs, and together they began attacking Alevi houses in the neighborhood. Official sources gave the number of Alevis killed as 57, with hundreds of injuries,” said Issa.

Others were mutilated by having their noses or ears cut off. Many victims were children and women.

Feyzullah Aygun, the head of the local branch of left-wing Labor Party, said, “When they announced that Alaaddin mosque was bombed, I also went towards the area. At that moment, police from their panzers, military commando brigades and fascists all shot bullets at us. Suleyman Atlas was lightly wounded on his left arm. We told him to come with us but they took him inside a panzer. Then they told us to lie on the ground. The commander of the military brigade told his troops to ‘shoot whoever lifts his head.’ Then a troop said that he shot one… I witnessed all of these things. The state has a great role in the escalating of the incidents and the slaughtering of the people.”

The prime minister of the time was Suleyman Demirel, the head of the Justice Party (AP), who later became the ninth President of Turkey.

1993 Sivas Massacre

On 2 July 1993, a crowd of fundamentalist Muslims set fire to the Madimak Hotel in Sivas Province, where Alevi intellectuals were staying to participate in a cultural festival. The attackers chanted “Allahu akbar” as the fire spread. Thirty-three intellectuals, mostly Alevis, as well as two hotel staff lost their lives in the fire.

The coalition government of the time was the True Path Party (DYP), a centre-right party, and the Social Democratic Populist Party (SHP), an Ataturkist, center-left party. And the Prime Minister was Tansu Ciller, who was also the first female PM of Turkey.

1995 Istanbul, Gazi Quarter Massacre

The massacre began with a series of armed attacks on March 12, 1995, on several cafés at the same time by anonymous persons with automatic rifle from a passing taxicab in Istanbul’s Gazi neighborhood, where mostly Alevis live.

As a result of the attack, Halil Kaya, a 67-year-old Alevi man, was killed and 25 people were injured. The perpetrators escaped unidentified after having murdered the cab driver, and set the hijacked cab on fire.

After the attack, many Alevi residents of the Gazi Quarter took to the streets in protest. On March 10-12, 1995, a total of twenty-two people were killed by Turkish security forces and around 300 injured in different locations, mainly in Gazi neighborhood.

The families of the victims took the Gazi and Umraniye case to the European Court of Human Rights. According to the report by the ECHR (Case of Şimşek And Others v. Turkey):

“Following this incident, residents of the neighborhood gathered on the street outside the cafes and in front of the Cem house [A meeting place for Alevis for social and religious gatherings] to protest against the indifference displayed by police officers after the shooting incident. People also gathered outside the hospitals, where injured people were being treated. At about midnight, the group, numbered in their thousands started marching towards the local police station. The police officers set up barricades with panzers and subsequently started attacking the group with their truncheons and the butts of their weapons.

Then two panzers approached the demonstrators and began firing at them. As a result, Mehmet Gündüz was killed on the spot and 10 persons were injured.

Snipers were positioned on nearby buildings, who targeted the protesters. During this firing, Fadime Bingöl and Sezgin Engin were killed and a number of others were injured.

Uniformed and plainclothes police officers, who had positioned themselves behind the barricades, on the side streets and on some of the buildings, fired intensively. For about twenty minutes the police officers chased a number of demonstrators who were trying to run away from the scene and shot them.

The police prevented the demonstrators from taking the wounded persons to hospital and attacked the crowd who were attending the funerals of Halil Kaya and Mehmet Gündüz.”

On March 15, the protests spread to a neighborhood in the Umraniye district of Istanbul. Five Alevis were murdered by security forces.

The ECHR decided that during the Gazi and Umraniye incidents, Turkey violated article 2 (the right to life), and article 13 (the right to an effective remedy) of the European Convention on Human Rights.

The PM was again Tansu Ciller, the leader of the DYP.

Alevis: Legally ‘Non-Existent’

Alevis were also exposed to deadly attacks in Ortaca, Mugla in 1966, in Elbistan, Maras in 1967, in Hekimhan, Malatya in 1968, and in Kirikhan, Hatay in 1971, among others. Alevis have been major victims of Islamic supremacism both in the Ottoman Empire and in Republican Turkey.

At the end of these massacres or pogroms, many Alevi residents had to leave their cities. Many business owners had to sell their businesses with prices much lower than their actual value. The ethnic, religious, and political structures of the once Alevi-populated areas were changed tremendously.

“If you go to the Kizilay city center in Ankara today and ask people if they are Alevis, the majority will deny it,” said Kemal Bulbul, an Alevi author and rights activist.

Bulbul explained that the reason is the systematic persecution and discrimination Alevis have been exposed to. “For what has been experienced cannot be erased from memories. Alevis were not only massacred in Yozgat, Tokat, Amasya, but also in Thrace and the Mediterranean. The Alevi dargahs (shrines built over the graves of revered religious figures) have been raided, plundered, burnt down, and destroyed.”

The population of Alevis in Turkey is estimated to be more than ten million, but the number is only approximate. As Alevis in Turkey are legally “non-existent”, no census has yet been conducted for them.

Apparently, the Turkish state and many of its Muslim citizens remember that Alevis exist only when they want to attack or murder them.

Source: Armenian Weekly

Link: Alevis in Turkey: A History of Persecution