Lyricism, Magic, and Graphic Medicine: An Interview with Dana Walrath

November 20, 2015Special for the Armenian Weekly

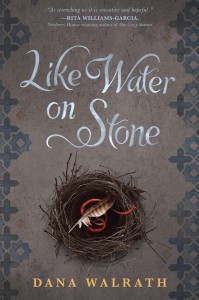

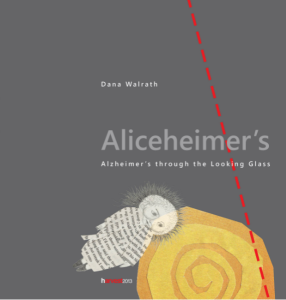

Meet author Dana Walrath. Born in Greensboro, N.C., and raised in New York City, Walrath’s heart has always been in Palu, her ancestral homeland. Her latest book, Like Water on Stone, is a heartfelt homage to the old country; a story of loss and new opportunities. Much has been the same for Walrath’s own life. Her mother’s struggles with Alzheimer’s disease led to their renewed relationship and the publication of Aliceheimer’s, a deeply personal graphic story that the author says “helps rewrite the dominant medical narrative of aging.”

Walrath’s Armenian upbringing wasn’t a typical one. She was raised to be an American, and only really “discovered” her Armenian roots later in life. A trip to Soviet Armenia in the late 1970’s and a life-changing trip to Western Armenia in the mid-80’s gave Walrath a renewed sense of identity and prompted her to begin a journey to tell the world her people’s story.

Her novel, which chronicles daily life in pre-1915 Palu and the genocide, isn’t your typical genocide book, either. Like Water on Stone, which is written completely in verse, is different than the many other novels with the backdrop of the Armenian Genocide. “So much of the genocide literature begins with disaster, and so you never get to linger on the beauty of the land,” she says.

Walrath’s grasp of the “beauty of the land” is spot on; she visited her lost homeland years before many Armenians began venturing back to Western Armenia. Walrath describes the trip as “an amazing time to be there,” even meeting a few Armenians along the way.

Walrath says she is committed to helping bring about real justice for Armenian Genocide victims—and she hopes her book can contribute to the process. “We’ve got to start with real conversation; really recognizing what happened and really finding ways to correct it,” she says. “I’m ready to go and talk about it in Turkey; I would love that opportunity. I think this book opens doors for those conversations.”

Walrath’s commitment to justice isn’t limited to the Armenian Genocide, though. She hopes that through her work, she is able to shed light on different global social justice issues. “I hope that my readers will see that connection and not fall into a trap of hating anyone after reading it… What we have to do is find like-minded people who know how to recognize justice and injustice, and we have to work together to really make things right in as many areas as we possibly can.”

The Armenian Weekly’s interview with Walrath follows in its entirety.

***

Rupen Janbazian: You were born in Greensboro, N.C., and grew up in New York City. In what ways was the Armenian culture a part of your upbringing?

Dana Walrath: I was born in North Carolina, but moved to New York City within the first weeks or months of life. So even though I could technically say I am a southern writer, I’m really a New Yorker at heart. My mother married an odar [non-Armenian], so my experience with the Armenian culture is very different. We had Armenian foods, without a doubt, and that was a real lifeline for us. Armenian music was also a big part of our lives.

There was a lot of tumult in my mother’s family. We saw relatives, but I didn’t know my grandparents; my grandmother died before I was born and my grandfather died when I was about five years old, so I only have hazy memories of him. There were some aunts and uncles, but my mother and her sister kind of grew apart, so there wasn’t really a big extended Armenian family. My mother wanted us to be Americans, and so we didn’t learn to speak Armenian at home. But it was present anyhow—how could it not be? I guess through the food and the music and the silence.

R.J.: The silence?

D.W.: I knew there was a genocide that had taken place, but I didn’t know any details. And it was the kind of thing that when I first learned about it, I didn’t know exactly how to process it. I remember asking my mother about her mother and she just said, very deadpan, that after [my grandparents] were killed, she [my grandmother] and Hopar and Uncle Benny and Aunt Alice hid during the day and ran at night from Palu to Aleppo. And I was a big map kid, so I went and got out the map and I was just blown away by it all. I just didn’t know how to process it all. I mean, you grow up around New York City, in the suburbs—we were in New Jersey at that point—and nobody’s grandparents were killed in hiding or running or any of that.

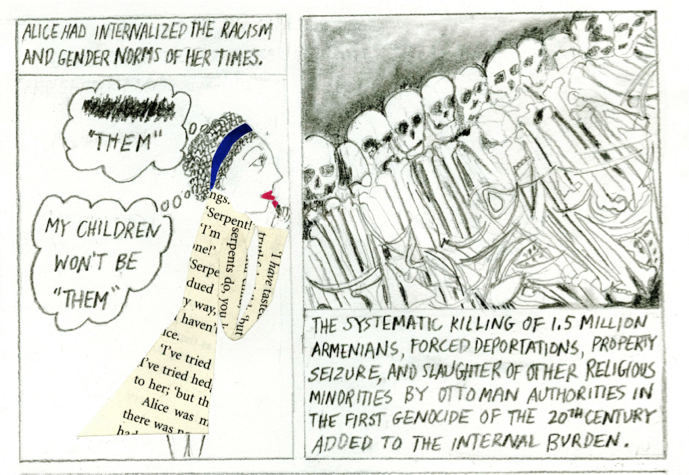

‘My mother wanted us to be Americans, and so we didn’t learn to speak Armenian at home. But it was present anyhow – how could it not be?’ (Photo: A page from Walrath’s Aliceheimer’s)

So I just put it to the side a little. I had an Armenian classmate in 5th grade and it was very clear that the other kids teased her. This is 1969-70, and America was still quite bigoted then. She was a little different, so she got picked on. I remember kids making fun of her name and things like that. I would go over to her house and play, but it was always sort of, “Well, do I fit in with the American kids, or this Armenian kid?” I didn’t go to Armenian school; I didn’t go to church, except occasionally for a funeral and a couple of weddings. We were raised outside the Armenian community, by and large.

R.J.: When was the first you heard about the genocide?

D.W.: The first conscious memory is hearing the story about my grandmother. That was a pivotal conversation. I knew [about the genocide] by the time I was in high school. I had a beloved history teacher and he asked me what he should know about the Armenian people, and I knew enough at the time to say, “Well, there was this genocide in 1915.” And I also knew enough to think, here is my smart history teacher who has been well educated—isn’t it unbelievable that he doesn’t know about it, that he’s coming to me and asking me about it?

Growing up around New York, I had many friends whose parents were Holocaust survivors, and so I knew from that experience that there was a bond; that very often, they knew the history, and so I felt a closeness and kinship that way.

In 1976-77, our family lived in Yemen on our way to Yerevan—that was sort of the way to make this trip. So even though it was silent, there was a yearning. My mother and father came up with this plan; my father had work there [Yemen] and they figured that we could go to Armenia on the way home. So there was a real effort to fill it all in.

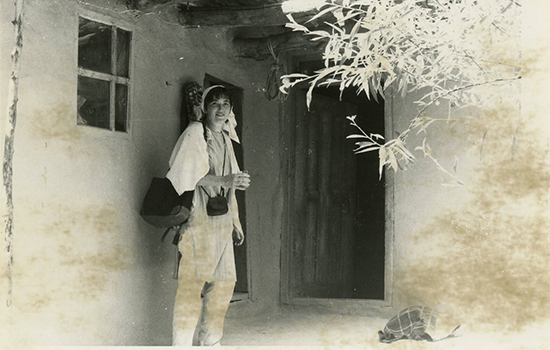

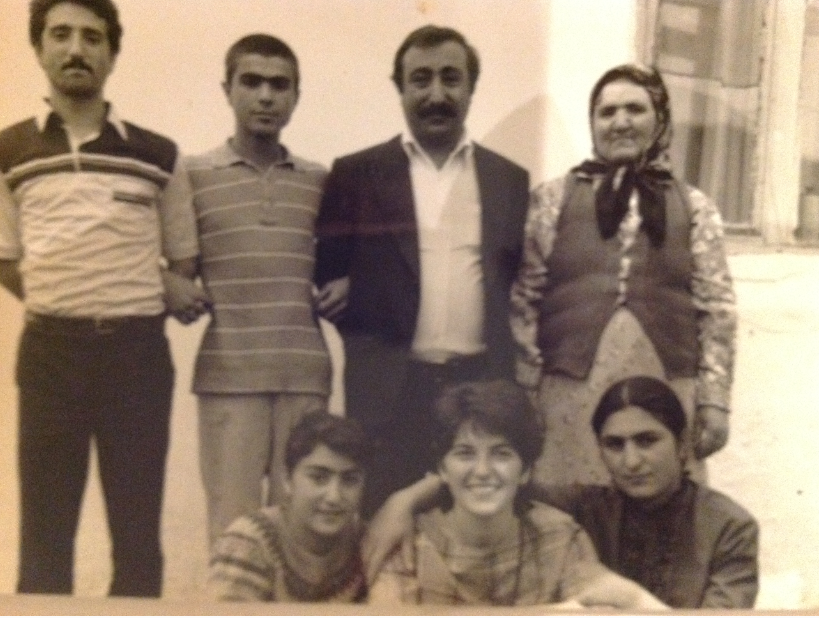

Walrath and family at Dzidzernagapert in Soviet Armenia, 1977 (Photo: used by permission of Dana Walrath)

R.J.: Your family story became the basis of the novel in verse, Like Water on Stone. Why did you choose to utilize prose instead of a more conventional style for the novel?

D.W.: When I started to write this book, it had begun as a two-generation story, going back and forth between immigrants in New York City and the old country. And the parts in Armenia came out in verse. I wasn’t committed to poetry, but it all sort of came out in fragments that I could slowly shape into a story. Then I realized that the two books needed to be separate, and so this one took off much faster; the other one is nearly done. Using free verse gave the opportunities to explore the really tough stuff, but to also give the reader and the writer the space to take it in and be surrounded by the lyricism and the magic of the magical realism as a way to really engage with it instead of running away.

I had many Armenians say to me that they just weren’t up for reading another genocide novel and that it took them a long time to get to my book, but then realized how different it was from the rest when they read it. I think that medium allowed me to go to different places with it. I also think that the medium conveys the distance between time and space and gives you a way to evoke this other world, and that’s powerful to have. Armenians say that they really want to know what life was like before the genocide. So much of the genocide literature begins with disaster, and so you never get to linger on the beauty of the land. I had traveled there in 1984…

R.J.: To Western Armenia?

D.W.: Yes. We rented a car in Paris; drove to Istanbul; took a ferry from Istanbul to Trabizon; drove down from Trabizon inland, all the way up to Artvin, Kars; then down Dogubayazet, Van; then across from Van to Mush; to Palu; to Kharput; to Konya; then down to the Mediterranean, up to Izmir, and left from there. It was an amazing time to be there because it was really early on—1984. It was at the height of ASALA [the Armenian Secret Army for the Liberation of Armenia], so I had to be very careful. I actually registered with the American Embassy. I just went there and said, “I’m an Armenian American, I’ve got a cult-identity. Shouldn’t be a problem.” I even traveled under my married name, so no one could suspect it at all, you know? We looked like a couple of young Americans.

R.J.: Not many Armenians were visiting Western Armenia back then.

D.W.: They weren’t. It was amazing—it really was, because we saw all the places. Armenian church after church, and it would just be labeled “church”; no real information. You go out to Akhtamar and everybody’s out there having picnics, but there was no mention of Armenians.

I did meet a local Armenian family in Kars. It was very powerful. We had gone to Kars to go to Ani, and back then Ani was prohibited, but we read that if you brought a carton of Marlboros, that the police would let you see it. They let us in, but were very strict about taking pictures—they wouldn’t let us do that. When we got back to Kars, we went to find the Armenian church, which was sandbagged and barricaded. There was a guy sitting by the church who started saying things in Turkish.

Now, my husband and I had learned a bit of Turkish so that we could get by on the trip, since back then it really wasn’t a tourist destination; no one spoke English and there were no real hotels. It was really the thing only 20-year-olds could do. The man started saying things like, “Ani was the capital of Armenia,” and “That’s an Armenian church… There used to be thousands of Armenians that lived here.” So I asked “Ermeni?” [“Armenian?” in Turkish], and he said yes. I explained to him that my mother was Armenian and that my father was American, so he grabbed the Turkish dictionary in my hand, flipped through the pages, and found the word to describe me. It was “mongrel.” It was great. He brought us to his home, and we met his mother, father, sisters. His sisters were actually weaving a carpet there. He told us he had spent some time in prison for his political activism. I really regret having lost touch with him. I still do have a photograph of the family, though. In this era of Facebook, I have to get it circulating in Kars and see if I can track them down.

‘He brought us to his home, and we met his mother, father, sisters…I really regret having lost touch with him. I still do have a photograph of the family, though.’ (Photo: Peter Bingham – Kars, 1984)

There was this other time in Istanbul. Whenever I first arrive to a new city, I love to just walk all over to get the lay of the land and a feel of the place. So after a really long walk, coming back to the Bosporus, an old man came out of a backgammon-raki sort of place—probably under the influence—and he was going [begins to beat her chest] “Ermeni! Ermeni!” telling us proudly who he was. We didn’t end up following up with him like we did the man in Kars, though, since there wasn’t an opportunity for that sort of quiet bonding. It was very public and involving raki, so…

Armenians say that they really want to know what life was like before the genocide. So much of the genocide literature begins with disaster, and so you never get to linger on the beauty of the land.

R.J.: Have you been back since?

D.W.: To Western Armenia? No, I have not been back. But I will be going in the next couple of years. I didn’t know it at the time, but since then I learned that my grandmother’s oldest sister had been married to a Kurd before the genocide started. I’ve heard different stories from my mother and my aunt. My mother’s version was that he was very good to her, and my aunt’s version was more like this was something ugly. I don’t know. But I do know that at the time of the genocide, she had two children—a son and a daughter—and she left with her son and left her baby daughter behind. And that daughter’s grandson tracked us down; he met my parents and other cousins. So he goes back and forth now between Antalya and the Netherlands. I’m dying to be back to the east with him and hear his version of history. So that’s something that’s on my horizon for next year, I hope.

R.J.: Going back to the book, why did you decide to narrate part of the story from the point of view of the Ardziv? Why the eagle and not another animal?

D.W.: There are a couple of reasons. I watched my trusted readers getting wigged out by the violence. It gets quite graphic in places—how could it not, considering the subject matter? I also noticed my readers struggle to track all the names of the characters, and so I felt I needed to simplify. So when I first wrote it, everyone spoke—you heard Fatmah directly saying hateful things; you heard from every member of the family. I realized I needed to simplify it, because although I was writing it for Armenians, I was also writing it for the story to be known to non-Armenians, for Americans. I was writing it for the refugees that have been living in Burlington, Vt., and thought that it would be good for them to see the story written by somebody whose grandparents had been through something similar and it brought us closer together.

I was looking for a way to simplify it, to make it safe, and to make it accessible. And so I knew I needed an omniscient narrator to help do that. The narrator makes it clear in his opening statement that it’s going to be OK to start a new life in a new land; that it’s not all going to be lost. I realized I needed the omniscient narrator who could be in many places at once; who could see long distances; who could track people while they were far below on the ground. It wouldn’t have worked to be any animal other than a bid of prey. Eagles—not just for Armenians, but for many cultures—embody strength and intelligence. Through the eagle, it gave me the opportunity to engage with what it means to be a hunter and to explore what kinds of killing is legitimate and what other kinds are atrocious. By having a hunter, there could be a distinction that way.

Of course, all the symbolism of the eagle for Armenians played into to it. It’s also interesting that the eagle is so important in the United States. That bird is beloved by many people because of its power, strength, intelligence, vision, and so forth. The more I learned about eagles, the more appropriate it was. I learned interesting facts, such as male eagles are always smaller than female ones. And here I have this story of twins, and the brother is so embarrassed that he’s smaller than his twin sister. It was so lovely and so fitting.

He brought us to his home, and we met his mother, father, sisters. His sisters were actually weaving a carpet there. He told us he had spent some time in prison for his political activism. I really regret having lost touch with him. I still do have a photograph of the family, though. In this era of Facebook, I have to get it circulating in Kars and see if I can track them down.

R.J.: What other sort of research went into the book?

D.W.: The research happened in two phases. After my trip to Armenia in 1977, I decided to learn everything I could about the history and the culture, so I read anything that was out there. And that’s sort of “early ages” for Armenian studies in terms of accessible books. I read The Forty Days of Musa Dagh, Michael Arlen’s book; basically, whatever I could. Then I started graduate school in anthropology in the 90’s and did some more research then and got very frustrated. I remember one academic article about the anthropology of Turkey, and it had a sentence in there about Eastern Turkey. It said, “…for some unknown reason the population of this region is not what it used to be at the turn of the century,” and I raised my hand and I said, scoffing, “There was a genocide perpetrated against the Armenians!” And I was at Penn, an Ivy League school, and he just ignored it! That scared me and I decided that I was not sure if I could take all this on. But I carried on.

When I was ready to write the book, I wrote the first draft free of research, because I just wanted to tell the story, to get out whatever was in my heart. After returning to it to check it over, I realized I had to make a number of changes. I had many standards on hand: [Peter Balakian’s] The Burning Tigris, Ronald Grigor Suny’s book. I was in Armenia at the time, and so I had access to everything at AUA [American University of Armenia] and the Genocide Memorial and Institute. I could really access many things. I ended up changing two major things. First, I had centered all the violence on April 24, considering the symbolism of that date. But when I started, really started, digging in and understanding the timeline of when exactly the violence came to Palu, I had to shift everything back a couple of months.

The other piece that changed was about Aleppo. After hearing my mother speaking about it, I had figured Aleppo was a haven, a safe place. The more I learned about it, the more I realized that the orphanages there were only really havens early on, and that the Ottoman government had later closed all of those and marched off the older kids and Turkified the younger ones.

The research didn’t stop there, though. I was absolutely delighted when I met Vahe Tachjian of Houshamadyan.org. It’s an amazing project. I used a lot of their resources, and what good fortune that the first city they opened with was Palu. Then I was in Yerevan, fully immersed in Armenian culture, so I had lots of daily life that, in a sense, became research of the anthropological, participant-observation type. I got very involved in folk dancing there and I already had a music-dancing thread in the book, but it could expand from me being there.

R.J.: What do you hope your readers take away from it all?

D.W.: What I hope the reader takes away is knowledge about the Armenian Genocide, so that nobody says something like, “Oh, this is controversial;” so that they’ll just say, “This happened, and the world has done nothing about it.”

I hope they also take away that there is a real distinction between governments and individuals, and that they don’t fall into the trap and say that all Turks are terrible—or all of any group of people is horrible, for that matter. What we have to do is find like-minded people who know how to recognize justice and injustice, and we have to work together to really make things right in as many areas as we possibly can.

I really feel like [the book] is important for the Armenian Genocide, but it also touches lots of global social justice issues. I hope that my readers will see that connection and not fall into a trap of hating anyone after reading it.

When my two sons visited me in Yerevan, we took a tour of the Genocide Museum. I remember our tour guide saying there was an Arab leader who said [that they should] help the Armenians—that just stuck with me, that there are allies at every turn. We need to celebrate those allies, because the courage that it takes to cross the boundaries to help others and to see what’s right is really important. I knew I wanted that thread in the book.

R.J.: Speaking about the distinction between governments and individuals, you’ve said in the past that you are committed to the movement for reconciliation between Turkey and Armenia. What does reconciliation mean for you? What does a future between the two countries and two people look like for you?

D.W.: I think that reparations are a big part of reconciliation. Recognition and reparations are part of moving forward. I don’t think that having those things gets in the way of having good relations; I think they are fundamental to it.

What exactly does that look like? I think Jermaine McCalpin is really good at laying out what reparations mean, how we can really make this happen. His framework is an excellent place to start, because it’s not insisting that if we don’t have this, then forget about it. It’s saying we’ve got to start with real conversation—really recognizing what happened and really finding ways to correct it. Very simple things. Obviously the recognition part of it, but also things like being able to buy land, for example.

I remember being in Palm Springs, Calif., and learning that the Native Americans owned the whole town and thinking about how, wouldn’t it be really nice if Armenians could go back [to Western Armenia] and buy land and be a part of a pluralistic society there if that’s what they chose to do. I also believe there should be some kind of material package to make up for all that was taken, and I really appreciate the work of scholars like Uğur Ümit Üngör, who are documenting that. Or the work of Taner Akçam that is showing what has happened, what the average Turkish child is learning in school. That to me is so fascinating—that if we reach a point where that [teaching of wrong version of history] is no longer happening, wouldn’t that be great?

I think that reparations are a big part of reconciliation. Recognition and reparations are part of moving forward. I don’t think that having those things gets in the way of having good relations; I think they are fundamental to it.

R.J.: For many years reparations weren’t really spoken about by the broader community; it was sort of the elephant in the room that people didn’t want to tackle. It’s been refreshing to see people talking about it recently.

D.W.: I found that to be very refreshing, especially at many of the [Centennial] commemoration events this year. I hope Like Water on Stone can contribute to all that, especially if it were to be translated into Turkish and Armenian. I’m ready to go and talk about it in Turkey; I would love that opportunity. I think this book opens doors for those conversations. I am approaching grandmotherhood and am not threatening to anyone and I can safely say things and have difficult conversations because I’ve got grey hairs and so forth.

R.J.: Your previous book, the graphic novel Aliceheimer’s, deals with your mother’s struggle with Alzheimer’s disease. You’ve described the book as “graphic medicine.” What do you mean by that?

D.W.: Graphic medicine is actually a field, a discipline that exists; it’s the use of comics to engage with healthcare in various ways. For some people, graphic Medicine is educational comic; for others, it’s writing memoirs about health experiences. Some very famous ones are Brian Fies’ Mom’s Cancer or David B.’s Epileptic.

Graphic medicine is a term coined by a physician and comic artist named Ian Williams. To me, this medium is so powerful because it relaxes people right away, since we associate comics with laughter, and being young. So we kind of go into it with open minds. It’s great, because you can show many things simultaneously in comics, whereas when you’re writing just in prose, it all has to unfold through time. When you’re looking at a page of a comic, you could have an image that contradicts what somebody is saying, and that happens all the time with health, because we’re embarrassed, and we’re afraid, and those things aren’t out there.

When I give lectures about it, I often reference a great graphic memoir called Blue Pill [by Swiss artist Frederick Peeters] about AIDS. The cartoonist is in love with a woman who is HIV positive, and they are talking with the doctor about what his risks are for contracting the disease. And the doctor says that it’s about as likely as walking out the office and getting run over by a rhinoceros. And then you turn the page and that’s what you see! It’s such a powerful medium for capturing the disconnect between what people really think and what they’re saying.

As an anthropologist, I know that medicine is about rules and rituals and things that we have to do and are supposed to do when we’re sick; graphic medicine is a sort of the counter-culture of all that. For example, with dementia, I think we have to rethink it completely. It’s an incurable disease right now and it’s beautiful that we’re raising money, and researching. But in the meantime, most of the memoirs are about the tragedy. I believe that doctors who approach families at the time of diagnosis, instead of saying that it’s a terrible thing, they should say, “Things are shifting, and it could be a real opportunity for you to do some really unexpected things.” That’s what I felt like I was allowed to do in my mother’s case. I was never all that close with my mother, and it allowed me to grow closer.

I remember our tour guide saying there was an Arab leader who said [that they should] help the Armenians—that just stuck with me, that there are allies at every turn. We need to celebrate those allies, because the courage that it takes to cross the boundaries to help others and to see what’s right is really important.

R.J.: It seems difficult to “find the light” in such dim situations though, no?

D.W.: It is. But if we find the light, then, no matter what happens, we can heal. In medical anthropology we make a distinction between curing diseasing and healing. Graphic medicine really gets into the story and the personal side of medicine, instead of the physiology and the mechanics. Healing happens when we understand each other. And so it ties back again in to the genocide—we heal by telling our stories.

When my mother was living with us, she ate up every graphic novel that came into the house. You think about something like dementia, where people are losing their words but continue to have a very strong visual capacity—those came to us first as human beings. I knew that when I was going to tell her story—when I was going to tell our story—I was going to use a medium that a person with dementia could access.

R.J.: You spent some time in Armenia as a Fulbright Scholar.

D.W.: I was in Armenia as a Fulbright Scholar for 10 months, from August 2012 through the end of June 2013. I returned in the fall of 2013 and did a TEDxYerevan talk there. I love going back to Yerevan. When you’re there as a Fulbright Scholar, the State Department asks you very specifically not to go to Artsakh [Karabagh]. And so when I was back in the fall, I finally went.

R.J.: Was that your first time in Artsakh?

D.W.: It was my first trip. It was beautiful, and amazing, and powerful. It definitely felt like a part of Armenia. It reminded me, actually, of forests up near Artvin; it’s very similar—the mountains and the woods and so forth. I really felt the Silk Road presence there, too, seeing all the mulberry groves and thinking about that. It’s really something to be there and to see Stepanakert, which is really a lovely city with such beautiful architecture. Then seeing this state-of-the-art airport that can’t be used, and thinking about all the issues going on. It was powerful. I was glad to go there then and will go again.

I was back in Armenia again this April for the premiere of the animation of Like Water on Stone, which was created by a team of students at Yerevan’s Tumo Center. I was also one of the authors at the Literary Ark Festival, and because of that, I was in the middle of everything for the Genocide Centennial commemorations.

R.J.: You were in Armenia for the commemoration?

D.W.: I was. I did the global forum, the convocation, saw the System of a Down concert—all of that. Going to the concert from Etchmiadzin [for the canonization of the martyrs] was an emotional rollercoaster. It was amazing.

So I was there for all of that, then got to go to China, where I was able to speak about both books. Chinese audiences know all about government suppression of history, but they knew nothing about the Armenian Genocide. They were fascinated and so grateful to know the story. It was really a lovely audience to speak with. And then I spoke about Aliceheimer’s there too—that’s what primarily got me there.

R.J.: Your research in Armenia was on Alzheimer’s?

D.W.: It was on the narrative anthropology of ageing in Armenia. So what I was looking at was what it was like to grow old in Armenia. I met with old people through Mission Armenia’s active senior groups; I met with two groups weekly, then I did home visits. You know, there are very few beggars in Armenia, but the vast majority of them are elderly, so I spent time in the street, talking to people. All of that is getting interwoven with the next Aliceheimer’s book that I’m working on, tentatively called Between Alice and the Eagle.

R.J.: How does Armenian society deal with a disease such as Alzheimer’s?

D.W.: There were two very contrasting responses to Alzheimer’s in Armenia. When I told people what I was doing, and told them about my mother’s dementia, I would have a lot of people say, “Oh, we don’t have Alzheimer’s in Armenia…we don’t have it at all!” And then I’d have people come up to me in private and say that they had such a terrible time with the disease, that it had happened to their mothers or fathers and they felt so alone and isolated.

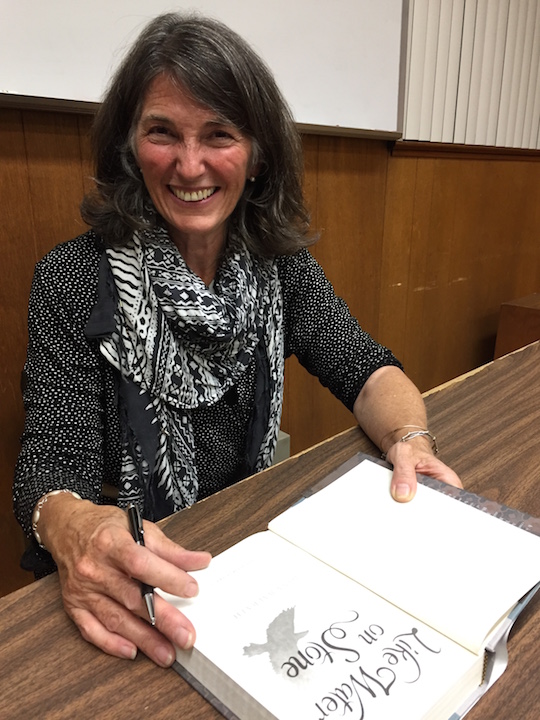

‘I’m ready to go and talk about it in Turkey; I would love that opportunity. I think this book opens doors for those conversations.’ (Photo: Holly Thompson)

The stigma surrounding any kind of disability in Armenia is huge. As North Americans, we can appreciate our privileges, and we’ve got so much that we can start really thinking about the rights of the disabled and removing the stigma from all sorts of things. It was a big battle to get to where we are here. Armenia is still working on lots of these kinds of diversity issues.

It was remarkable for me to see how few disabled people I would see on the streets there. It was only when I volunteered as a tidort [elections monitor] in Yerevan’s municipal elections that I was exposed to a large number of disabled people in the city. I must’ve seen more that day than I did the whole year, and that’s a problem. They are very isolated.

I interviewed many physicians while in Armenia and they said that this stigma exists for any kind of neurological condition. People are hiding it at home, and people that loved each other end up hating each other. It’s really difficult to do it alone, especially when it’s not spoken about.

R.J.: You mentioned plans for an upcoming book. Anything more concrete you can tell us?

D.W.: The upcoming Aliceheimer’s book or the…

R.J.: How about both?

D.W.: [Laughs] How about all three! Right now I’m mostly working on a book called Life it Gives, a New York City immigrant story. I hope I’ll be able to tell you when that one is coming out fairly soon. The North American edition of the Aliceheimer’s book is coming out very soon, and then the next edition, I’ve been working on bits and pieces of it. In the meantime I’ve got another novel called The Garbage Man, about hoarding disorder—it’s a contemporary, U.S. novel, nothing to do with Armenia. I wanted to make sure people knew me as a writer who was bigger than one issue, because I feel like that really strengthens the other issue. That will have drawings in too, but will not be in comics form. The next Aliceheimer’s book will be in strict comics form.

R.J.: We look forward to reading them.

D.W.: I look forward to keep sharing.

Source: Armenian Weekly

Link: Lyricism, Magic, and Graphic Medicine: An Interview with Dana Walrath