Russia’s Humanitarian Response to the Armenian Genocide

May 20, 2016Humanitarianism and the Refugee Crisis on the Caucasus Battlefront During World War I

The Armenian Weekly Magazine

April 2016

By Asya Darbinyan

Introduction

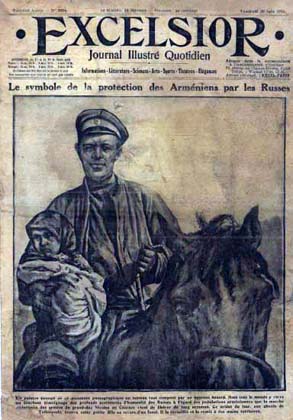

Cover of the June 30, 2016 issue of ‘Excelsior’ carried an illustration of a Russian soldier on horseback with a refugee child in his arms. The picture was captioned, ‘The Symbol of Protection of the Armenians by Russians.’

The front page of the June 30, 1916 issue of the Parisian newspaper “Excelsior” carried an illustration of a Russian soldier on horseback with a refugee child in his arms. The picture was captioned, “The Symbol of Protection of the Armenians by Russians.”1 The words “Russia” and “humanitarianism” are rarely coupled in the historical literature on the 20th century. This essay, however, emphasizes the importance of exploring imperial Russia’s reaction to the Armenian Genocide and the refugee crisis on the Caucasus battlefront of World War I. It shows how the recognition of an emergency situation transformed political and public reaction into action, and how the Russian imperial government during the Great War and the Armenian Genocide—as well as a number of non-governmental organizations established in the Russian Empire—provided humanitarian assistance to hundreds of thousands of Armenian refugees in need. It also plumbs the motivations for humanitarian assistance and the Russian context of humanitarianism.

The Great War and the Armenian Genocide

While Russian and Ottoman imperial troops fought on the Caucasus front of World War I, hundreds of thousands of Ottoman-Armenian subjects were targeted by Turkish authorities as a potential “strategic threat.” Justifying their actions as militarily necessary, the Ottomans massacred the Armenians or deported them to the deserts of Mesopotamia. Those who did not fall victim became refugees on the Russian-Ottoman battlefront. Armenians suffered numerous hardships during all of the Russo-Turkish wars of the 18th and 19th centuries, but the war that started in fall 1914 had unprecedented consequences for the Armenians, particularly for the Ottoman or Western Armenians. This time the consequences were catastrophic, as the Armenians fell victim to a systematically implemented genocide under the cover of World War I by the Ottoman state.2

The Great War began in Europe in July 1914; the war over the Straits and on the Caucasus front between the Ottoman and Russian empires unrolled in November 1914.3 The murder of Armenian peasants and priests, and the wiping out of entire villages on the Russian-Ottoman border, ensued. German missionary Dr. Johannes Lepsius put the number of Armenian victims in these frontier zones at 7,0004 in November-December 1914. As Armenian Genocide scholar Raymond Kevorkian has observed, “the majority of the massacres took place before [War Minister of the Ottoman Empire] Enver launched his offensive [on Sarikamish, Kars province, Russian Empire, on Dec. 22, 1914].”5

Official Political Reaction of the Russian Empire

Reports about the Turkish atrocities against the Armenians quickly reached the Russian Empire. Mikhail Papadjanov, the Russian State Duma representative for the Baku, Yelizavetpol, and Erivan6 regions, claimed in his July 1915 speech in the Duma that the Turks had targeted Armenians in the bordering regions of the Caucasus front before Russian troops had even entered, annihilating them as “an element having close ties with Russia.”7 Papadjanov, like many other statesmen in the Russian Empire, attempted to bring the Turks’ violence against the Armenians to wider attention. By spring-summer 1915, the Russian Empire’s southwest—Transcaucasia—was flooded with tens of thousands of Armenian refugees and internally displaced persons who had been forced to abandon their homes in the Russian-Ottoman border regions (Kars, Ardahan, Olti, Ardvin, Alashkert, Basen, and other towns).

In addition to the Armenians displaced by pre-war incidents and then warfare between the two empires, new waves of genocide refugees from the Ottoman Empire were expected every day.8 These were Armenians who had escaped the massacres and deportations organized by the Turkish authorities in various parts of the Ottoman Empire. According to Armenian Genocide scholar Taner Akçam, the first deportations of Armenians living in the Ottoman Empire began in February 1915,9 and gained momentum in the months that followed. As historian Ronald Suny has explained, “Deportations ostensibly taken for military reasons rapidly radicalized monstrously into an opportunity to rid Anatolia once and for all of those peoples perceived to be an imminent existential threat to the future of the empire.”10 The nation-wide deportation and annihilation of Armenians began in April-May 1915 and continued during the entire period of the Great War.

The official response of the Russian Empire to the horrifying developments both in the Ottoman Empire and on the Caucasus front was immediate condemnation. Russia’s joint declaration with Great Britain and France in May 1915 is perhaps one of the best-known documents of the time. The powers defined the atrocities against the Ottoman Armenians as a “crime against humanity” and promised to hold members of the Ottoman government and those “implicated in massacres personally responsible” for those crimes.11 Yet, little is known about the role played by Sergey Sazonov,12 the foreign minister of the Russian Empire, in drafting this declaration. Sazonov proposed public condemnation of the Ottoman government for the slaughter of its Armenian subjects, and engaged the British and French diplomats in this process. “The dynamic of internal reporting on the massacres [of Armenians] caused the Russian government to initiate the joint Allied note,”13 Peter Holquist, an expert in Russian and modern European history, has explained.

A series of undertakings followed the joint declaration. Sazonov reflected on the massacres in his July 1915 speech to the State Duma. “Armenians suffer unprecedented persecution,” he emphasized.14 The persecution and the refugee movement that ensued were tragic for the Armenian people and highly problematic for the Russian civil and especially military authorities, whose first goal was to win the war. Russian political and public figures not only protested Ottoman violence, but also pressed for relief work to confront this emergency situation.

Humanitarian Assistance by Relief Committees and Organizations

A number of committees and organizations were engaged in the Armenian refugee relief effort, among them the Committee of Her Highness Grand Duchess Tatiana Nikolaevna, the All-Russian Union of Towns, and the All-Russian Union of Zemstvos.15 These organizations, along with the Russian Society of the Red Cross (RSRC) and national committees, including various Armenian benevolent organizations, participated in refugee assistance on the Caucasus front. Most of the Russian organizations were established as war relief committees to assist the wounded and sick on the frontlines. With the influx of hundreds of thousands of refugees into the interior of the Russian Empire, these institutions developed into refugee and orphan care organizations.16

The Tatiana Committee, established on Sept. 14, 1914, by Her Highness Grand Duchess Tatiana Nikolaevna, the daughter of Tsar Nicholas II, and chaired by State Senator Aleksei Neidgardt, was a major initiative.17 Among the committee’s main responsibilities were providing one-time financial support for refugees; assisting in repatriation or resettlement, as well as refugee registration; responding to inquiries from relatives; and arranging employment and housing assistance.

The state treasury supported the activities of the Tatiana Committee, and donations from various institutions, committees, and individual donors offered significant sums.18 The committee also deployed the power of the press and placed appeals in newspapers to raise money. As a result, by April 20, 1915, it had raised 299,792 rubles and 57 kopeks (about $150,000).19 Acknowledging the potential of artistic events in promoting fundraising, the Tatiana Committee hosted charity concerts, auctions, performances, and exhibitions. A.I. Goremykina, the wife of the prime minister,20 organized an arts night in Marinskii Palace on March 29, 1915, which was a great financial success. An auction of paintings by famous Russian artists brought the Tatiana Committee 25,000 rubles from that one event alone.21

The All-Russian Union of Towns was another major relief institution. Founded in August 1914, it quickly grew into a large organization with branches in a number of towns all over the empire. Its main task was to aid the wounded and sick on the frontlines, and establish infirmaries, evacuation centers, meal stations, and hospitals.22 With the escalation of war and opening of the Caucasus front, the union’s responsibilities expanded to assisting refugees who were streaming into the Russian Empire in great numbers. A branch, the Union of Caucasus Towns (later, the Caucasus Department), was founded in Tiflis in September 1914 under the auspices of the Caucasus viceroy.23 All of the major towns in the region that joined the Caucasus branch soon opened infirmaries. The Special Central Bureau, consisting of Alexander Khatisov [Khatisian], the mayor of Tiflis, and the mayors of other major towns, was to coordinate the organization’s activity. The Caucasus Department had several tasks: evacuation of the wounded and sick, transportation of the refugees from the frontline to the interior, establishment of meal stations, sanitary-medical assistance (particularly prevention of epidemics during humanitarian operations), and collection of donations (especially for its clothing depot).24

The All-Russian Union of Towns worked in cooperation with the All-Russian Union of Zemstvos, established on July 30, 1914.25 By the middle of 1915, the Zemstvos Union had also turned to providing for the welfare of large numbers of refugees, many of whom remained in areas under military jurisdiction. The cooperation between these two unions lasted until 1916, when the Zemstvos Union ceased refugee operations because of strained relations with government officials.26

The Russian Society of the Red Cross was one of the most powerful and successful organizations in the Russian Empire in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. By summer 1914, some 39,000 people worked for the RSRC, including 1,000 physicians and 2,500 nurses.27 The RSRC opened hospitals on the war fronts, including the Caucasus front, and established hundreds of infirmaries, soup kitchens, and evacuation centers. It operated sanitary trains and vehicle squads responsible for transporting the wounded, as well as disinfecting squads to prevent the spread of highly contagious diseases. The RSRC’s Printing Bureau,28 responsible for its publicity campaign, informed the entire population of the Russian Empire about the work of the organization, spurring a great number of donations. Some of these funds were used to assist the Armenian refugees on the Caucasus front and in the interior of the empire.

Government Coordination of Refugee Assistance

Refugee humanitarian activity and financial affairs fell to the Ministry of Internal Affairs, and were coordinated by the Special Council for Refugees in Moscow (Osoboe soveshchanie po ustroistvu bezhentsev),29 which was established on Aug. 30, 1915. The council disbursed funds for refugee relief (the initial plan allotted 25,000 rubles); oversaw the registration and relocation of refugees; assisted in the return of refugees to their place of permanent residence; arranged loans; ascertained the value of property refugees had been forced to abandon; compensated refugees for losses incurred as a result of military action and for property that had been requisitioned; and addressed the spiritual and educational needs of refugees.30

The decree defining “refugee” status was issued on Aug. 30, 1915. “Individuals who left the localities threatened or already occupied by the enemy, or were deported from the military zones at the command of either military or civil authorities, as well as individuals originating from Russia’s enemy states, are to be identified as refugees,” it read. But “individuals deported from the military zones under police oversight” were not to be regarded as refugees.31 All individuals identified as refugees were supposed to be issued a refugee card or book, which accorded them privileges (access to soup kitchens, financial and medical assistance). At the same time, the authorities recorded the travel routes and workplace changes of the male or female heads of refugee households. The Minister of Interior appointed General Tamamshev32 plenipotentiary for the organization of relief efforts for the refugees on the Caucasus front; he served as the head of the Department for Refugees on the Caucasus Front until May 1917.

Condition and Number of Refugees on the Caucasus Front

As many as 120,000 to 150,00033 refugees passed through the Ottoman-Russian border in summer and fall 1915. The Caucasus Department opened meal and tea stations, as well as medical stations on the Igdir–Etchmiadzin–Erivan–Yelenovka–Dilidjan–Aghstev34 route for refugees coming from Turkey. The relief organizations aided the refugees transported to and sheltered in the Caucasus internal regions, particularly in the Erivan and Yelizavetpol provinces. When the war escalated, Armenian refugees on the frontline as well as in the regions occupied by Russian troops (in Igdir, Van, Bitlis, and later Erzurum) also received substantial assistance.35

Etchmiadzin, the Armenians’ religious center, became a major refugee town in the Caucasus. The number and condition of the refugees were alarming, and the need for assistance urgent. “Number of refugees [in Etchmiadzin] is 30,000; [daily] death toll is above 300. Five hundred corpses remain not buried. Healthy refugees have scattered in panic,” reported Khatisov, the head of the Caucasus Department, on Aug. 29, 1915.36 Soviet economist and demographer Evgenii Volkov elucidated the dynamic of the refugee movement in the Caucasus, claiming that within the Caucasus viceroyalty on Jan. 1, 1916, there were 220,800 refugees; by May 1, 1916, that number had decreased to 179,200, then climbed to about 182,000 to 185,900 by June 1, finally peaking on Nov. 1, 1916, when there were 367,000 registered refugees in the Caucasus.37 Because of the great number of refugees, Russian relief agencies welcomed assistance from Armenian local and national organizations, such as the Etchmiadzin Committee of Brotherly Aid, Armenian Central Committee of Tiflis, and the Armenian Red Cross Committee in Moscow.

Russian Motivations for Relief Work and Plans for Armenian Refugees

The Russian Empire had complex motivations for assisting Armenian refugees on the Caucasus front. Because of the variety of actors engaged, there were a variety of agendas. Reflecting on the origins of humanitarianism and the various motives behind humanitarian action—psychological, biological, and utilitarian, among others—scholar of international relations Michael Barnett asserts, “Humanitarianism has many mothers.”38 My preliminary research suggests that in addition to the humanitarian sentiments and compassion felt in Russian governmental circles as well as among ordinary people, many other factors came together, such as the need to resolve the emergency caused by the refugee crisis in order to secure Russian military success; adherence to the policy towards other ethnic-religious groups in the empire during war; historic ties between Russians and Armenians; and the self-perception of the Russian Empire as the protector of all Christians in the region.

The Russian Empire had a vast Armenian population in Transcaucasia, spreading from the Kars region to the Black Sea coast and Tbilisi, and from the Caspian Sea and Baku to the Russo-Iranian border. The empire’s policy had not always been favorable towards Armenians; in fact, it fluctuated over time in response to economic, political, and military concerns, as well as geopolitical developments in the region. Changes in Russian policy, especially after 1912, led to the empire’s active involvement with the Armenian reform project, which aimed to improve the condition of Ottoman Armenians.39

According to diplomat and scholar Manoug Somakian, the shift in Russian policy towards the Armenian reforms occurred for several reasons. First, the Russian Empire planned to use the oppressive rule of Ottoman-Christian subjects in favor of its interests in the Straits. Then, too, it aimed to deploy the Armenian Question, and through Turkish Armenia control northwest Persia also. Russia’s pro-reform policy would regain40 the loyalty of its Armenian subjects and prevent anarchy in Transcaucasia. And finally, if accomplished, this policy could compensate for the Russian Empire’s disastrous defeat in the Russo-Japanese War of 1905 by success elsewhere.41 Responding to developments in the Ottoman Empire and on the front, as well as unflagging appeals by Armenians to intervene to stop the violence, the tsar in 1914 assured the Armenian Catholicos that “a brilliant future awaited Armenians,” and that after the war “the Armenian Question will be resolved in accordance with Armenian expectations.”42 The condition of Armenians, however, would deteriorate as the war unfolded.

To understand Russian motivations, we must plumb the Russian Empire’s plan for the refugees and the occupied eastern territories of the Ottoman Empire. Pointing to the colonization plan of Minister of Agriculture Krivoshein, the Armenian historian Avetis Harutyunyan argues that a Russian anti-Armenian position was obvious from the beginning of the war. Krivoshein presented his project to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in February 1915, and suggested settling Erzurum, Van, and Bitlis with Cossacks to promote the colonization of Western Armenia and to support the Caucasus 4th Army with food supplies.43 Historian Peter Holquist, by contrast, argues that Krivoshein’s project was only a suggestion, not state policy.44 He believes that the Russian government did not have a coherent plan or project for those regions when the war was waged, and that annexation was not considered or confirmed officially at that point.45 Manoug Somakian also mentions Russia’s colonization projects, and the resettlement of Cossacks in the occupied areas. He raises another crucial question: Why did the Russian authorities in some instances prohibit the return of Armenian refugees to their homeland, now occupied by Russian troops? Somakian claims that the “intended policy was to settle Cossacks in the vilayets of Erzurum and Trabzon, and entry was to be prohibited to Armenians.”46 He emphasizes that permission to return to the valleys of Alashkert, Bayazid, and Diadin was granted only to native inhabitants who could show their right to property or land, or to conclude purchase contracts.47 These preconditions and requirements made the return of refugees to their homes highly problematic and in many instances impossible. The majority had lost their documents and papers when they fled.

Holquist holds that urgent military interests, rather than an anti-Armenian policy or a colonization plan, shaped those decisions. “The need to supply the army, rather than to prepare the land for Russian colonization, lay behind the army’s management of Armenian and other refugees,”48 he argues. Elaborating further on this point, Holquist explains that the developments in the Russian-occupied eastern provinces of the Ottoman Empire were no different from policy elsewhere at the time, and did not target Armenians alone.

Colonization had been a common policy in various regions of the Russian Empire for centuries. Speaking about Russian colonial practices and the use of Cossacks and Russian settlers in the Caucasus, Siberia, and Central Asia, genocide scholar Donald Bloxham explains that it “was a standard method of consolidating control of conquered regions.”49 Russian Empire historian Robert Geraci reflects on the tsarist plan to “clean” the north-east Caucasus area of Muslim tribes and to “replace them with Cossacks and other Russian settlers who would be reliably loyal.”50 Those practices, however, were typically directed against the non-Christian peoples of the Russian Empire or against those identified as “unreliable” subjects. But Armenians did not belong to either of those groups. Thus, addressing and analyzing Russian plans for Armenians both in Russia’s interior and in the occupied territories of the Ottoman Empire will shed light on the motivations behind the Armenian relief campaign.

Conclusion

Exploring Russian response to the Armenian Genocide is key to analyzing refugee movement as a result of the genocide in the Ottoman Empire and the warfare on the Caucasus front during the Great War, and to scrutinizing the dynamics of the refugee crisis by delving into core questions of motivation, decision-making, and implementation of relief work by Russian civil and military authorities.

The remains of Armenian children, drowned in the Black sea, Trabzon, 1916 – Photo – Armenian Genocide Museum and Institute Collection

The Russian government defined the category “refugee” by law and assigned aid accordingly. The law, however, was adopted only in August 1915, months after the flow of refugees into the empire’s interior. The efficiency of assistance during that initial period, as well as the influence of the new regulations on relief work afterwards, calls for more research and analysis. The relationship between the relief agencies and the government, as well as between various agencies, also yearns for further study. The Tatiana Committee, supported by government circles and the nobility, appears to have enjoyed great advantages. Yet, the All-Russian Union of Towns and the All-Russian Union of Zemstvos, operating in the military zones, developed trusted relations with the military authorities. Scrutinizing these relations will provide a new perspective on the peculiarities of relief work on the Caucasus front.

Finally, regarding the motivations of the Russian authorities to launch such intensive humanitarian and relief work for the Armenian refugees, Canadian academic and former politician Michael Ignatieff holds, “Humanitarian action is not unmasked if it is shown to be the instrument of imperial power. Motives are not discredited just because they are shown to be mixed.”51

The Great War itself was a challenge to humanitarianism. The early years of the last century were marked by economic changes. New sources of capital investment in philanthropy shifted the contemporary understanding of philanthropy and humanitarianism. The concept of charity evolved into philanthropy, and emergency relief turned into long-term development programs. Elucidating the complexity of Russian humanitarianism during the Great War will prompt us to recontextualize the Russian Empire’s policy and will shed new light on the meaning and nature of humanitarianism in the beginning of the 20th century.

Notes

[1] Excelsior, Paris, France, June 30, 1916.

2 For a history of the Armenian Genocide in the Ottoman Empire, see Taner Akçam, Young Turks’ Crime Against Humanity: the Armenian Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing in the Ottoman Empire, Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2012; Vahakn N. Dadrian, The History of the Armenian Genocide: Ethnic Conflict from the Balkans to Anatolia to the Caucasus, Providence, R.I.: Berghahn Books, 1995; Raymond Kevorkian, The Armenian Genocide: A Complete History, New York: I.B. Tauris, 2011.

3 Mustafa Aksakal, The Ottoman Road to War in 1914: The Ottoman Empire and the First World War, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008, p. 17.

4 Kevorkian, p. 220.

5 Ibid.

6 Yerevan, the capital of the current Republic of Armenia, was spelled Erivan in official documents of the Great War era.

7 The Genocide of Armenians: The Responsibility of Turkey and the Obligations of the World Community. Documents and Commentary, Yuri Barseghov, ed., vol. 1, Moscow 2002, p. 251 [Russian].

8 Reports submitted by representatives of various Russian organizations provide information about the number of refugees on the Caucasus front. On his visit to the Caucasus in August 1915, Kishkin, a member of the Head Committee of the All-Russian Union of Towns, reported the number of refugees at 150,000. He emphasized that it was the second time since the beginning of the war with the Ottoman Empire that Transcaucasia was seeing such a huge flow of refugees from Turkish Armenia; the first wave was a result of the Turkish troop offensive in December 1914, while the second came in July 1915, after the sudden retreat of Russian troops from the vilayet of Van (see Bezhentsi i vyselentsi. Otdel’nie ottiski iz No17 Izvestii Vserossiiskogo Soiuza gorodov, Moskva, 1915, pp. 83, 88). The report by Ionnesian, the commissioner of the Baku Committee for Refugee Relief, stated that by October 1915 in Erivan province there were up to 93,000 displaced persons, and 165,000 in Erivan and the other provinces together (see A.G. Ionnesian, Polozhenie bezhentsev v Aleksandropol’skom raione, Baku, 1915). Peter Gatrell mentions that by the beginning of 1916, at least 105,000 ex-Ottoman Armenians had sought refuge in Erevan alone and that the total number of Armenian refugees tripled during the following 12 months (see Peter Gatrell, A Whole Empire Walking: Refugees in Russia during World War I, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2005, p. 26).

9 Taner Akçam, A Shameful Act: The Armenian Genocide and the Question of Turkish Responsibility, New York: Metropolitan Books, 2006, pp. 145-46.

10 Ronald Grigor Suny,‘They Can Live in the Desert but Nowhere Else’: A History of the Armenian Genocide, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015, p. 245.

11 Kevorkian, p. 763.

12 Sergey Sazonov was the Russian Empire’s Minister of Foreign Affairs from November 1910 to July 1916.

13 Peter Holquist, “The Origins of ‘Crimes Against Humanity’: the Russian Empire, International Law, and the 1915 Note on the Armenian Genocide,” unpublished paper, presented at the conference, “From the Armenian Genocide to the Holocaust: The Foundations of Modern Human Rights,” University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mich., April 2-4, 2015.

14 The Genocide of Armenians, Yuri Barseghov, ed., p. 249.

15 A zemstvo was an elected provincial or district council established in most provinces of Russia by Alexander II in 1864 as part of his reform policy.

16 See Peter Gatrell, A Whole Empire Walking: Refugees in Russia during World War I, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2005; Russian local government during the war and the Union of zemstvos, T.I. Polner, et al., New Haven: Yale University, 1930.

17 GARF (Gosudarstvennyi Arkhiv Rossiiskoi Federatsii), f. 651 (Tatiana Nikolaevna Romanova), op. 1, d. 39, 1.11.

18 Bakhurin Yu, “Tatianinskii Komitet: 1914-1917,” Starii Tseikhgauz, no. 52 (no. 2/2013), p. 48.

19 GARF, f. 651, op. 1, d. 39, p. 1.

20 Ivan Goremykin was prime minister of the Russian Empire from February 1914 to February 1916.

21 GARF, f. 651, op. 1, d. 39, p. 1.

22 Kratkii otchet o deyatel’nosti Kavkaszkogo otdela Vserossiiskogo soiuza gorodov pomoshchi bol’nym i ranennym voinam (Tiflis, 1915), p. 1.

23 The union was incorporated into the Caucasian department of the All-Russian Union of Towns on Nov. 9, 1914.

24 Kratkii otchet o deyatel’nosti Kavkaszkogo otdela Vserossiiskogo soiuza, pp. 18, 37-39.

25 Gatrell, p. 235.

26 GARF, f. 5913 (Astrov Nikolai Ivanovich), op. 1, d. 2a, p. 352.

27 O.V. Chistiakov, “Rossiiskoe Obschestvo Krasnogo Kresta vo vremia Pervoi mirovoi voiny,” Voenno-istoricheskii zhurnal, no. 12 (2009), p. 67.

28 Ibid.

29 Rukovodiashchie polozheniia po ustroistvu bezhentsev, Petrograd, 1916, p. 1.

30 Zakony i raspolozheniia o bezhentsakh, Vypusk 1, Moskva, 1916, p. 5.

31 Zakony i raspolozheniia o bezhentsakh, Vypusk 1, Moskva, 1916, p. 2.

32 Avetis Harutyunyan, “Hai gaghtakanutian teghabashkhume yev ognutian kazmakerpume Arevmtian Haiastanum Mets Yegherni tarinerin,” Etchmiadzin, no. 4, Etchmiadzin, April 2002, p. 86.

33 Kratkie svedeniia o polozhenii bezhentsev na Kavkaze i okazannoi im Soiuzom gorodov pomoshchi za vremia s 20 sentiabria po 1 noyabria 1915g. (Tiflis, 1915), p. 11.

34 Ibid.

35 Harutyunyan, pp. 81-91.

36 As quoted in Bezhentsi i vyselentsi. Otdel’nie ottiski iz no. 17, p. 91.

37 E.Z. Volkov, Dinamika narodonaseleniia SSSR za 80 let, Moskva-Leningrad, 1930, p. 70.

38 Michael Barnett, Empire of Humanity: A History of Humanitarianism, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2011. For approaches to motivations for humanitarian action and intervention, see also Michael Ignatieff, Empire Lite: Nation Building in Bosnia, Kosovo and Afghanistan, London: Vintage, 2003; Weiss, Thomas, Humanitarian Intervention: Ideas in Action, Cambridge; Malden, Mass.: Polity Press, 2007; Wheeler, Nicholas J., Saving Strangers: Humanitarian Intervention in International Society, Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.

39 For the Armenian reform project, see Andre Mandelstam, Le sort de l’Empire Ottoman, Paris, 1917; Roderic H. Davison, “The Armenian Crisis, 1912-1914” in the American Historical Review,

vol. 53, no. 3, April 1948, pp. 481-505.

40 The oppressive Russian stance towards Armenian political organizations in the early 1900’s had compromised the Transcaucasian Armenians’ trust in imperial Russia’s policy.

41 Manoug J. Somakian, Empires in Conflict: Armenia and the Great Powers, 1895-1920, London; New York: Tauris Academic Studies, 1995, pp. 46-48.

42 Suny, p. 230.

43 Avetis Harutyunyan, “Tsarizmi gaghutain kaghakakanutiune Arevmtian Haiastanum (1914-17), Baikar Armenian Monthly, v. IV, no. 5-6 (May-June 1996), p. 31.

44 Peter Holquist, “The Politics and Practice of the Russian Occupation of Armenia, 1915 – February 1917”, in Suny et al. (eds.), A Question of Genocide: Armenians and Turks at the end of the Ottoman Empire, New York: Oxford University Press, 2011, p. 155.

45 Holquist, p. 154.

46 Somakian, p. 98.

47 Ibid, p. 109.

48 Holquist, p. 168.

49 Donald Bloxham, “Internal Colonization, Inter-imperial Conflict and the Armenian Genocide,” Empire, Colony, Genocide: Conquest, Occupation, and Subaltern Resistance in World History, ed. by Moses, Dirk, New York, Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2008, p. 331.

50 Robert Geraci, “Genocidal Impulses and Fantasies in Imperial Russia,” Empire, Colony, Genocide: Conquest, Occupation, and Subaltern Resistance in World History, ed. by Moses, Dirk, New York, Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2008, p. 347.

51 Michael Ignatieff, Empire Lite: Nation Building in Bosnia, Kosovo and Afghanistan, London: Vintage, 2003, p. 23.

52 For a history of humanitarianism, see Michael Barnett, Empire of Humanity: A History of Humanitarianism, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2011; Bruno Cabanes, The Great War and the Origins of Humanitarianism, 1918-1924, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014; Didier Fassin, Humanitarian Reason: A Moral History of the Present, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2012; Humanitarian Intervention: A History, ed. by Simms, Brendan & Trim, D.J.B, Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011; Keith David Watenpaugh, Bread From Stones: The Middle East and the Making of Modern Humanitarianism, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2015.

Source: Armenian Weekly

Link: Russia’s Humanitarian Response to the Armenian Genocide