From the Armenian Weekly 2018 Magazine Dedicated to the Centennial of the First Republic of Armenia

Zaruhi Bahri is one of the many women who need to be written back into Armenian history. Despite her decades-long activism and prolific writing, she is all but invisible in current scholarship. If one of the reasons for her absence in historiography is her sex (Armenian historiography largely remains blind to women’s experiences), the other is the long silence on the history of Armenians who stayed in Turkey in the immediate aftermath of the Genocide, the years that Bahri was most active in the Constantinopolitan Armenian community.

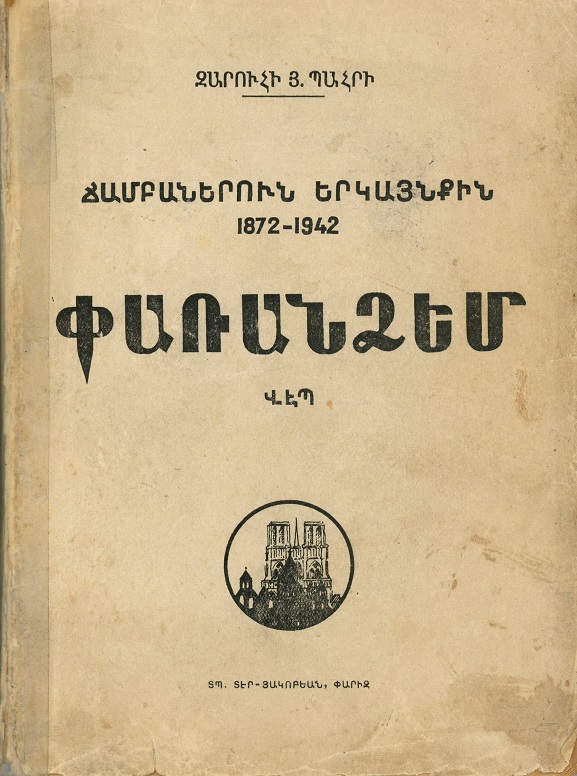

After moving to France in the late1920s, Bahri wrote six historical novels, all of them featuring female protagonists. One novel is specifically about the life of an Armenian woman during and after the Genocide, but the remaining works revolve around Armenian life either in pre-Genocide Constantinople or post-Genocide France.[1]

All but one of the works devoted to the history of literature in the Diaspora ignore her existence.[2]

Accordingly, in this special issue dedicated to the centennial of the First Republic of Armenia, I give the floor to Zaruhi Bahri to tell us how she, from her corner in Istanbul, observed and interpreted the fate of her kin in Transcaucasia from 1918 to 1921. The selections come from her memoir, Gyankis Vebe (The Novel of My Life), which was posthumously published by her family in Beirut in 1995. A more extensive translation will appear in Feminism in Armenian: An Interpretive Anthology (edited by Melissa Bilal and Lerna Ekmekcioglu, forthcoming in 2020). Published and unpublished works of hers, as well as interviews with her descendants, will appear in Feminism in Armenian’s website in digitized form.

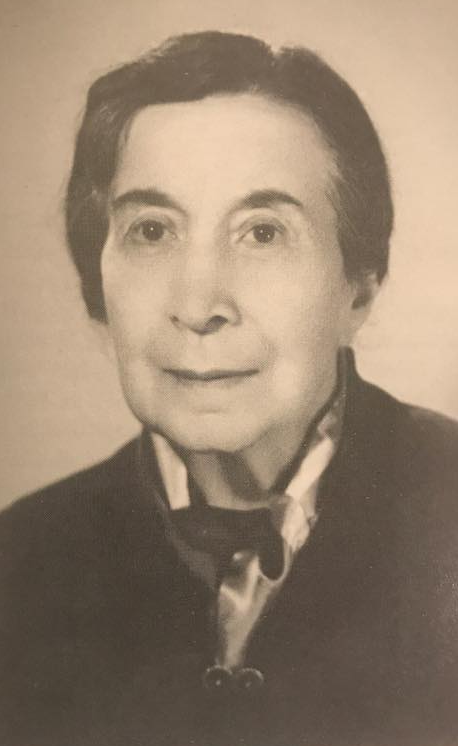

Zaruhi Bahri: A Short Biography

Zaruhi Shahbaz Bahri was born Constantinople on May 31, 1880. She began her work in the public space after the 1909 Adana massacres. She taught orphaned girls sewing and needlework. During the 1912-1913 Balkan Wars, she worked in charitable organizations that provided the families of Ottoman Armenian soldiers with food and clothing. She was one of the women who established the Armenian Red Cross of Constantinople in 1913

Zaruhi lost a brother and sister to the Armenian Genocide. Her sister was deported from Amasya (a city in north-central Turkey, in the Black Sea Region) with her family, after which they all disappeared. Her brother, Parsegh Shahbaz, a member of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (Hay Heghapokhagan Tashnagtsutiun), was among the intellectuals arrested by the Ottoman government on the night of April 24, 1915, and later killed.

The Bahri family spent the war years in the Ottoman capital. After the Mudros Armistice of Oct. 1918, the Armenian residents of the city were most active in relief work for survivors who came to the capital from Mesopotamia and other parts of the Middle East. Very soon after the signing of the armistice, Bahri became director of the Shishli branch of the Armenian Red Cross of Constantinople and a member of the Armenian Women’s Association (AWA). She also began contributing essays to the women’s journal Hay Gin (Armenian Woman). At the Armenian Patriarch’s request, she worked as the Armenian representative and director of the Neutral House (Chezok Doun, Bitarafhane) where orphans and young women of contested identities were brought in order to determine whether they were Turkish or Armenian. When the Turkish Kemalist forces entered Istanbul and forced the Allied evacuation, Zaruhi Bahri had to flee the city with her family, for she was viewed as an anti-Turkish figure because of her work at the Neutral House (accused of “Armenianizing Turkish children”). The family first escaped to Bucharest and, later, in 1928-1929, moved to Paris.

Together with her husband Hagop Bahri, a prominent lawyer, she had four children and four grandchildren. She died in Paris on May 13, 1958, and was buried in Père Lachaise Cemetery. In 1987, in accordance with her wishes, her children took her ashes to Armenia to bury them on the grounds of Etchmiadzin Cathedral, the Mother Church of the Armenian Apostolic Church.

***

Translations from Gyankis Vebe

Part I

Zaruhi Bahri and her family, along with many other Armenian intellectuals who were not deported from Istanbul, spent some parts of the war years on Kınalı Ada, one of the Prince Islands near Istanbul, which used to be known as “Hay Gghzi” (Armenian Island), for it was heavily populated by Armenians. In this section of her memoir, Bahri narrates hearing the news of the establishment of the Republic of Armenia in 1918.

- The Independent Republic of Armenia (p. 156-158, translated by Deanna Cachoian-Schanz)

And so, this historical moment and our generation were destined to witness the establishment of our long dreamt-for country (hayrenik). From its very first day, we were aware of the problems that our small, newly formed state would face. But the sheer fact that even our greatest and perhaps only enemy, the Turks, recognized it—albeit under pressure—assured us that we could overcome all obstacles as long as we continued our stubborn work. And, indeed, the Turkish newspapers delivered us the good news. True, that small country wouldn’t satisfy our greatest wishes, but we trusted in the benevolence of our great Allied friends to satisfy the rest. We were not interested in the specific political and military conditions under which that republic was given to us.

I confess that we were enveloped by a childish, intuitive, and reckless happiness, and we openheartedly surrendered ourselves to the enchantment of that joyous gift. Poor Hrant Asadour was the only one who couldn’t ardently savor that long-awaited, long-desired joyous news. The mental illness that had already taken hold, and which in the end would overcome him, filled him with a fear that rendered all of our encouraging words and factual arguments utterly futile. He would retire to his bedroom and withdraw behind closed windows and doors not to hear or take part in the ardent enthusiasm of the young people outside, which inundated the rocky paths of the Armenian island.

The enthusiasm in our house knew no limits. The blood of our lost loved ones and of the hundreds of thousands of martyrs was finally emerging victorious from this unequal battle.

A celebration was to be organized in the village hotel.

The Arakelian sisters were going to play, my Noyemi was going to recite Chobanian’s “To Armenia,” and Mannig Berberian was going to sing “Armenia, Heavenly Land” wrapped in a tricolor flag. I don’t know how we knew that the Armenian flag was the red, blue, and orange tricolor. We were still at war and it was very difficult to find colored fabric. We succeeded in finding dye and we sacrificed a bed sheet to prepare a large, beautiful flag for our bright new fatherland (hayrenik).

The celebration took place with indescribable enthusiasm. At everyone’s request, Shahan Berberian took the floor and fervently praised our fatherland (hayrenik).

As I write these lines in one of the distant suburbs of Paris in the autumn of 1952, I recall with great pleasure that one evening not too long ago I had the pleasure of hearing “Armenia, Heavenly Land” sung again, this time by a young Armenian from Marseilles, which brought a flood of different emotions back to my mind’s eye. That song was quite dear to my precious mother, who would softly hum it to me when I was a child, when the tyranny of Sultan Hamid had yet to end. My adolescent children sang it until the dawn of the Ottoman Constitution [1908]—until 1914 arrived seeking to destroy my ancient nation in a reign of terror. So it was sung for the emancipation of Armenia, in those perhaps deceptive days, on a rocky island in the Sea of Marmara, expressing the fervor of a patriotic group.

And now it is sung in my émigré’s apartment in Boulogne, it is sung by a youth born and raised on foreign soil. I’ve heard that precious hymn from the lips of four generations, praising glory to our fatherland. “Will a fifth generation that grows up abroad continue to sing it?” I asked sadly.

“Yes, madam, you can rest assured,” said the precious youngster, and added, “our generation won’t be lost because now we have a homeland, an actual country toward which we fix our eyes and hearts each time we recite the words Armenia, heavenly land.” And as if to complete the meaning of his words, he began to enthusiastically sing, “Blossom Free, My Homeland.” My eyes welling with tears, I kissed that dear ambassador of the new, foreign-born generation.

Part II

In this section, Zaruhi Bahri narrates developments that led to the Sovietization of Armenia.

- “The Fatherland is in Danger” (p. 179-182, translated by Maral Aktokmakyan)

During that summer of 1920, the news of the realities in Armenia gradually began to grow unclear. The statements of the national assembly slowly ceased to be reassuring. Stormy winds were blowing, casting down our enthusiasm. In a speech to an overflowing audience in the Petit Champ theater, A. Khadisian brought the reality before us: In Armenia, there was no food, no clothing, no medicine, no guns… and no money. We were looking in vain for a powerful state that would protect this small, suffering republic whose people, desiring emancipation, were unmercifully slaughtered and crucified, while those who survived had given their best to the benefit of those powerful countries.

At the start of autumn, Turkey began to become a threatening force under Mustafa Kemal’s resurgent forces and, as always throughout their history, the Armenians became the first victims in those horrific days. The surprising irony is that in the occupied capital of the very same Turkey, our newspapers still enjoyed the freedom to write about Kazim Karabekir’s assault [against Armenia] and the dangers threatening our fatherland.

It was then that I thought that it is every Armenian’s duty to send at least some financial support to the threatened fatherland. The easiest and most practical way was to donate a military tax to the state in place of our children who did not serve as soldiers in the army. I sent an article entitled “The Fatherland Is in Danger” to [ARF publication] Azadamard (Battle for Freedom) or its successor, the newspaper Jagadamard[3] (Battle). Along with it, I sent 50 golden coins each for my two children, Krikor and Jirayr, in lieu of their military service. My Krikor was studying in Paris, and my Jirayr, my poor, precious Jirayr, barely 15 years old, desperately wanted to volunteer in the Armenian army… But how? Armenia, surrounded by enemies, wasn’t even able to breathe…

A black curtain was being drawn on our two years of enthusiasm, emotion, and hope… The fatherland wasn’t in danger: It was on its deathbed…

***

That black curtain would be pulled back on a supposedly gloomy morning in November with Armenia’s lustrous Sovietization. The brotherly army coming down from the North told Kazim Karabekir’s hordes, “Hold off there!” It was Stalin’s immortal voice that ordered from Tiflis that “Armenia must be helped.”

The tears of sorrow were replaced with tears of joy. Those who had hesitated to believe in the past now had difficulty in accepting the reality.

For instance, during those days I received a visit from Dr. Torkomian, a great friend of my husband and our family. I had noticed that he held me in high esteem since the time that a very short article of mine titled “But I Have Still Been Waiting for You,” which I wrote to the memory of my brother, appeared in Jagadamard.

Dr. Torkomian visited to talk to me about a particular matter. Perhaps he wished to clear his conscience by getting my assent. He noted that on the same morning he had received a check of ten thousand francs from Mrs. Aharonian in Paris, to be delivered to the army of Armenia, and he added sadly that he was obliged to send back the money right away as we did not have an army any longer and the “Reds” occupied Armenia a day or two ago. I protested severely. For us, for our family, Armenia, whether red, blue, or yellow, was ours and so was its army. And he made a mistake in having sent back the money because that money could have been used to satisfy a need. It is true that a short while after this we would be thrilled to hear that the Soviet government from Moscow provided a large amount of material aid to our small Sovietized republic, while the Allied governments had denied Free Armenia any pounds sterling or dollars. This, despite Fridtjof Nansen’s request with tearful eyes before the League of Nations Assembly in Geneva, where he said, among other things, “You will save a people, an entire nation for the yearly cost allocated toward just a single battleship of the great nation that is England.”[4] And the Assembly remained deaf to the supplicant call of that great philanthropist.

Moscow became an unconditional provider for Armenians. And the Armenian people, supported financially and protected against the external enemy, raised up their country with energetic hard work and creative mind to amazing heights in 30 years, to most people’s surprise. It is painful, and even more than painful, that some of us still insist on going against the course of history.

***

Thereafter we had gradually been receiving news of Kemalist troops’ victories over various lands in Asia Minor. How pleasant it was to think that the direction of Kazim Karabekir’s soldiers had been directed westward, where this time they unfortunately faced the Greeks who had landed there after the Armistice of Mudros. The Allies were still in Istanbul, where one would see twice a week the parade of Scottish soldiers with picturesque uniforms, feathered caps, and rustic band. The bandmaster on the front would swing his astonishing decorative instrument and give beats for his musicians to play. To safeguard against any maritime or ground attack, Mustafa Kemal had made Ankara the capital city, that Turkish city in the center of Asia Minor, where even its Armenian population was Turkophone.

I don’t wish to talk about politics, thinking that, without evidence, my views might be subjective and might not correspond to the truth.

We were trying to continue to do our work. The Armenian Patriarchate, National Caretaker Service (Azkayin Khnamadarutiun), Armenian Red Cross, Neutral House (Chezok Doun), each one of them did their part conscientiously and faithfully.

Part III

In this section Zaruhi Bahri narrates the ARF’s rebellion against the Bolsheviks in Armenia that began on Feb. 18, 1921 and was suppressed on April 2, 1921. Coming from an ARF family, Bahri is critical of the uprising and supports the Bolsheviks because she sees the Soviets as the only force that will protect Armenia from Turkish attacks.

- Armenian Women’s Association (p. 192-193, p.194-197, translated by Maral Aktokmakyan)

[…]

In the summer of 1921, the reality of Soviet Armenia was becoming increasingly more reassuring. Government representatives were coming to Istanbul to report on that reality and forge connections with most of the Armenian communities abroad and inspire faltering minds with strength and faith.

I am happy and proud that as much as our home, the Shahbaz-Bahri family, had been among those that sacrificed much to the cause of Armenianness—had lost its members and had been ground down—it also knew equally well how to appreciate and deeply experience the joy of the liberated fatherland, no matter that it constituted only a fragment of the (territorial) rights that we had been claiming. Our home was one of the first to receive the leaders of Soviet Armenia.

[…]

In the fall of 1921, I left with Jirair for Paris via Italy, by boat up to Naples, at which time I met and talked with B. Boissière, the French scientist I wrote about in the section on the Neutral Home (Chezok Doun), then to Rome, Venice/San Lazarro, Turin, and through the Alps on to Paris.

Having read Ruskin’s works and D’Annunzio’s Le Feu, I set off, ready to meet the aesthetical wonders awaiting me in Italy. Communing with the Old World and the works of Renaissance masters, my soul was enlivened with boundless satisfaction. On the other hand, I pitied our people, the Armenian nation, which had its own multifaceted riches, but whose similar aesthetic works had been the target of barbaric Asiatic invasions and destroyed. But I remained hopeful, only because I truly believed in the eternal soul of my race, like a rising phoenix. I believed that under the watchful supervision of Moscow, and without internal dissent, the fatherland and its people would find their path upward, toward luminous horizons.

Before having any rest after that unforgettable journey, a great national-political disappointment was in store for us. That was the February Uprising. I know that there were people, many people, who wanted and still want to give a share of responsibility to the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF) for the Turkish policy of the extermination of Armenians in the 1915-18 period. They claim that ARF should have been more cautious, and could have taken a prudent step to, if not forestall, at least to mitigate the ferocity of the horrible crime. I do not think they should have the right to criticize men who consciously absolved themselves of their misdeeds by sacrificing their lives. Making mistakes is a human trait. Insisting on mistakes is a crime.

Mr. Saghatelian, a member of the Duma of Tsarist Russia, would tell my husband years ago in Istanbul: “Our mistake was to believe that we could deceive imperial Turkey and defeat her by relying on Europe. We did not realize that politics never entails humanitarianism, we never thought that every leader is obligated to look after the interest of his own country and people. We failed to see that Turkey was founded on a 500-600-year tradition of military discipline, that its leaders had a mentality of ruling, whereas our revolutionaries are the children of a nation that has degenerated (aylaserads) under centuries-long enslavement. Thereby, though committed, they are unable to compete with their adversary.”

Based on this, and judging from the ARF leaders I had known in the past and as well as the conduct of my brother Parsegh, I did not want to believe that Armenians, those committed ones who are dubbed as patriots in Armenia, after enduring all the disappointment that our two Delegations (to the Paris Peace Conference), Patriarch Zaven (Der Yeghiayan), Fridtjof Nansen and our friends suffered as they defended our case in the conferences and the League of Nations Assembly,[5] would betray recently established Soviet Armenia, which was going to survive thanks to the new regime that shook the world.

In Paris I had, at times, the opportunity to see Avedis Aharonian, whom I had met in Istanbul. During those meetings, I shared with him my views [about the political situation]. He would not oppose what I was saying. But I have the deep belief that his illness, which caused occasional brain congestion, was the main reason why, during a banquet, in response to a question, he felt obliged to make a statement in favor of the anti-Armenia policy of his political party. I was so convinced by his patriotism, I thought he must return to Soviet Armenia at the first occasion and continue his activism and literary career there (just as Avedik Isahagian would do in the following years). I tried to make his life a little easier. I introduced him to my cousin, Vahan Khorasanjian, inviting them and Mrs. Aharonian to a tea party in Neuilly, Dr. Karakoch’s residence. That first encounter was followed by a dinner that Khorasanjian hosted in Hotel d’Iena. After that, Khorasanajian became friends with him in the broadest sense of the word, and remained friends during Aharonian’s long period of illness.

Based in particular on what I had told him, Khorasanjian respected Aharonian as a poet, a man of letters, a great patriot, the president of the first government, and future ally of the newly established Soviet administration. As proof of his great sympathy for Soviet Armenia, he [Khorasanjian] donated a large and most valuable Aivazovsky seascape to the museum in Yerevan.

The February Uprising ended, with the result being18,000 casualties from among this unfortunate people who had already been bled to death. Fortunately, though, the uprising ended with the victory of the Soviet regime. Who among us could imagine, without fearful uneasiness, about a possible scenario where the ARF laid claim to the conditions on the ground? Turkish hordes were on the border, ready to smash, destroy, ruin everything, to the very last…

As I write these lines, my entire being shivers from the horrors of new perils. I am terrified by the Americans’ assistance to improve the Turkish army and economy.[6] Trained under the supervision of American officers and armed with the latest weapons, Turkish soldiers are a great threat to the other side of the Arax river.

But why not take heart by the sole remaining hope, with our poetess Silva Kaputikyan’s hope that “henceforth the road to Yerevan goes through Russia”?

Notes

[1] Her genocide novel is Parantsem: Jampanerun Yergaynkin (Paris: Der Hagopian, 1946). Others: Dakre: Vospori Aperun Vra 1875–1877 (Paris: Der Hagopian, 1941); Dayyan Kevork Bey gam Badriarkarani Poghotsin Pnagichnere: Vospori Aperun Vra 1895-1898 (Paris: Le Solei, 1952); Muygerun Dag (Beirut: Madensashar “Ayk,” 1956); Louisette ou Osmose (serialized in Aysor: 1952); Ambrob (serialized in Azad Khosk, Paris: 1940). Bahri also edited and wrote the introduction of the book that her son Gerard Bahri wrote, Vahan Maleziani Gyankn u Kordse: Hushamadyan Ir Utsunamyagin Artiv (1871-1951) (Paris: Le Solei, 1951).

[2] Bahri does not appear in the Soviet Armenian Encyclopedia or in the Armenian Abridged Encyclopedia. Notwithstanding a couple of factual mistakes, Krikor Beledian discusses Bahri’s works in his Fifty Years of Armenian Literature in France (California State University, Fresno, DATE, edited by Barlow Der Mugrdechian, translated by Christopher Atamian), p. 393-395. Beledian does not see talent in Bahri’s works, finishing her section with “The author, simply stated, doesn’t seem to possess the talent to achieve her ambitions.” (p. 395). Beledian does not shy away from noting, however, that other critics during the time of Bahri’s novels’ publication found her work “the cornerstone of the new Armenian novel, the best example of the genre,” as stated by Yenovk Armen in Loossaghpiur, March 1953, no 7, p. 180, as quoted in Beledian fn 23 on page 395.

[3] Zaruhi Bahri’s note: I don’t have a copy, as it was destroyed like all my other papers, in Istanbul. It must of course be in the [newspaper’s] archives (author’s note).

[4] Lerna Ekmekciglu (L.E.) Note: Zaruhi Bahri uses the word “zrahavor” (in Turkish, zırhlı) which means “armored.” While in time it came to mean “soldier,” during the time of Bahri’s writing it usually referred to ships with extensive armor. I thank my friend Ulys for alerting me to this nuance as well as his careful reading of and comments on this whole text.

[5] Here Bahri says “azkayin zhoghov,” meaning “national assembly,” but she must have meant “azkerou zhoghov,” meaning “assembly of nations”—i.e., League of Nations Assembly.

[6] Bahri refers to the Marshall Plan here.

The post A View from the Bosphorus: Zaruhi Bahri’s Take on the First Republic of Armenia and Its Sovietization appeared first on The Armenian Weekly.

Source: Armenian Weekly

Link: A View from the Bosphorus: Zaruhi Bahri’s Take on the First Republic of Armenia and Its Sovietization